Back in the bad old days, wars were fought with armies and guns and bombs and killing people. Warfare of this type has not ended, but fortunately it has become less common than in the past, especially among advanced countries. Modern war is fought with sanctions and debt and conditional loans and devaluations. Or so it seems sometimes, especially in the latest showdown over austerity and the Grexit.

In the psychology of old-fashioned warfare, countries were prone to war fevers. Some insult would inflame people's national pride and get everyone worked up into a state of patriotic rage absolutely demanding a war. No doubt they would go in with illusions, expecting a quick and easy victory and seriously underestimating the hardships involved. Yet those hardships, at least initially, would not undermine people's resolve, but stiffen it, as people became enraged at the hostile power that was hurting them. Only when war grinds on and on, with no end in sight and no seeming prospect of victory do people get tired of it.

So I am very curious to see if the same psychology applies to modern "warfare." Certainly we have many of the same ingredients here -- an intolerable threat to a nation's sovereignty, a humiliating ultimatum, a stronger power determined to dictate terms to a weaker one and on terms that seem to rub the weaker power's nose in its weakness. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has framed the referendum as saying yes or no to the latest austerity package. Like today's Republican Party speaking of negotiations with Iran, he insists that the alternative to the present deal is not war (or Grexit), but a better deal.* Does he believe it? Do the people of Greece believe it? Some may, but given the extent to while the Europeans have been shouting at the tops of their lungs that rejection means Grexit, I have to think that, while some may have illusions, most know what is at stake. So the real question is, does war fever psychology apply here? Will a week of frozen bank accounts and the prospect of surging import prices and external debts, shrinking savings, and an at least temporary and severe economic crash have the power to intimidate far beyond the mere prospect of bombs falling, cities shelled and people killed? I don't know.

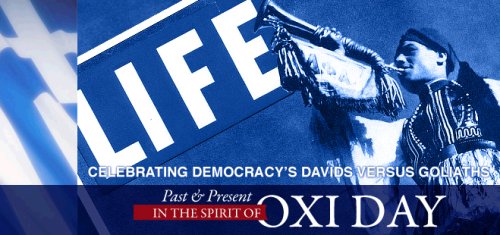

I do know that my own, unknown and unheeded, advice to Tsipras was to be a demagogue, to give a shameless, chest-thumping reassertion of national sovereignty, and to invoke the memory of WWII. And lo and behold, he appears to be doing just that. Syriza is framing the upcoming referendum as voting yes or no to a humiliating ultimatum and is holding rallies calling on the people to vote "Ohi," or No.** And this, it turns out, has strong resonance

for anyone seeking to stir up patriotic fervor. Greece entered WWII after Italy made a deliberately humiliating and unacceptable ultimatum, demanding that Axis forces be allowed to enter Greece to occupy certain unspecified "strategic locations." Greece's leader responded, in French, "Alors, c'est la guerre." (Then this is war). But Greeks preferred to believe that he answers, in Greek, simply "Ohi!" or No!

Greeks across the political spectrum poured out into the streets shouting Ohi! Great patriotic fervor ensued and a rush to war. And, in fact, the Greeks gave the Italians the Axis' first defeat, at least in a land war before being utterly crushed and suffering to a degree far beyond the worst that could possibly follow in the wake of any Grexit. That day (October 28) has been celebrated as a patriotic holiday in Greece ever since, despite the horrors that followed. So the whole "Vote No" referendum may be an attempt to stir up a sort of "war fever" in a way not immediately apparent to outsiders.

*Actually, to be fair to many Republicans, it may be that they genuinely don't want war, but just want to continue sanctions (modern warfare) as statement, however futile, of disapproval. Certainly no one is proposing that we invade Cuba any time soon or attempt the violent overthrow of the Castros, but Republicans are dead set against lifting sanctions on Cuba because they make a statement, long after they have been proven futile.

**Greek is apparently an exception to the usual Indo-European rule that words of negation begin with "n." In Greek, they begin with "o." I have been trying to leave allusions to Classical Greece out of my posts on modern Greece, but this one is hard to resist. In the famous cyclops story from the Odyssey, Odysseus tells the cyclops that his name is "No one" so that when he is putting out the cyclops' eye and the cyclops screams in pain, the neighbors ask who is hurting him and the cyclops says "No one!" Well, it appears that the Greek word for no one is "outis," which sounds a little like "Odysseus."

No comments:

Post a Comment