So, Robert Bork is dead. Admirers recall him in characteristically admiring terms, while opponents set aside the normal reluctance to speak ill of the dead. I can make a few comments.

The Bork nomination fight was not as unprecedented as people say. It is commonly said that the Senate was doing something new and unprecedented when it rejected Bork as a nominee for Supreme Court, but that is simply not true. Richard Nixon had two nominees rejected for the Senate before successfully appointing Harry Blackmun, and encountered considerable resistance to William Rehnquist.

The Bork nomination sent Supreme Court nominations downhill -- but that was all, Conservatives these days often argue that our dangerous polarization today began with the Democrats rejecting Bork for the Supreme Court. If only they had confirmed Bork, Republicans seem to imply, all the polarization that happened since -- the two government shutdowns under Clinton, the Clinton impeachment, Bush v. Gore, the abuses of the filibuster, the debt ceiling crisis, and Republicans' current willingness to crash the whole system in order to destroy Obama -- could have been avoided. This story sound way too much like the abusive husband claiming that he only beats his wife because she provokes him. I will concede conservatives this -- the rejection of Bork has totally ruined the Supreme Court nomination process. Prospective nominees since Bork have refused to give straight or honest answers to the Senate for fear of meeting his fate. But I do not believe that all the polarization that has happened since can be laid that the door of the Bork nomination. To call the hysterical behavior of Republicans for the past two decades payback for Bork is an extreme case of overkill.

I could live with the Bork of The Tempting of America on the Supreme Court. After being turned down for the Supreme Court, Robert Bork wrote three books, The Tempting of America, Sloughing Toward Gomorrah, and Coercing Virtue. Of the three, I have not read Coercing Virtue. The Tempting of America expresses a controversial but defensible viewpoint -- that the Constitution should be interpreted according to its text, as understood at the time of adoption, and that the Supreme Court should not read new rights into it. This is a tough enough standard that even Bork is not always able to live up to it. Most famously, he endorses Brown vs. The Board of Education in its finding that school segregation was contrary to the Fourteenth Amendment, even though the practice was widely accepted when the Fourteenth Amendment was passed. His reasoning is, in effect, that the phrase "equal protection of law" was written to ensure racial equality and must be interpreted with that end in mind -- but that our concept of racial equality does not have to remain frozen in 1868. But he is so uncomfortable with this conclusion that it takes him three paragraphs to say so. His discomfort is understandable. If our concept of racial equality does not have to remain frozen in time, who knows what else might not have to remain frozen, either.

Bork also can't quite bring himself to endorse a ban on any school, public or private, teaching foreign languages to children before the eighth grade (Meyer v. Nebraska), a ban on Catholic schools (Pierce v. Society of Sisters), or state legislatures so grossly malaportioned that a majority is systematically excluded from electing a representative majority (Baker v. Carr). He appears, however, to be willing to tolerate punishing some crimes with coerced sterilization (Skinner v. Oklahoma), to say nothing of a ban on contraceptives (Griswold v. Connecticut). I am inclined to support Bork's essential thesis -- that no matter how bad the law, the Supreme Court may not strike it down unless it violates a specific clause of the Constitution -- though not his application in many cases. And for an originalist who says we must follow the wishes of the Founding Fathers, he discusses them with a refreshing lack of romanticism or idealization.* Only when he starts discussing the people who opposed his nomination does Bork's tone begin to veer off into authoritarianism or paranoia. Bork disagrees with his opponents, such as the ACLU, public interest advocacy groups and so forth, obviously. Such disagreement is understandable. But never does Bork seem to acknowledge that such people might hold their views in good faith, or that they have the right to advocate for them, after all. Ultimately, he seems to regard the mere existence of liberal advocacy groups and sinister and basically unacceptable.**

But the Bork of Slouching Toward Gomorrah scares the hell out of me. But if The Tempting of America is controversial but defensible, Slouching Toward Gomorrah veers off into crazyland. Bork does not just lament that society is heading downhill on greased runners, he seems to think that the entire Enlightenment was a huge mistake. Not only does he condemn equality (with the grudging exception of equality before the law) as an evil that only a sinister elite favors, but even liberty seems to him like a dubious value. The whole book reads like a longing to return to the Middle Ages, when intellectuals were securely in the pockets of the ruling elite and were paid to defend the status quo of power, not criticize it, and when any too-stubborn dissident who could not be bribed faced the possibility of burning at the stake.

It was from Bork that I learned that authoritarianism is not the same as statism. Bork appears to concede democratic government as an inevitable evil, but want to limit its scope and be as authoritarian as possible in everything else -- families, churches, schools, workplaces, and so forth. Incredibly, for a book written within a decade of the end of the Cold War, Bork says almost nothing about Communism -- and what little he does say borders on favorable. He applauds Communists for banning rock music, saying that they understood that it was a threat to all authority. If today's pop culture was what brought down the Berlin Wall, he would just as soon see it go back up again. While I believe that Jonathan Haidt is right to criticize liberals for dismissing conservative concerns for group loyalty, authority, tradition, and sanctity as mere authoritarianism, in Bork's case, the accusation looks accurate. Bork sets a high value on authority and tradition and is dismissive of freedom. He also strongly seems to suggest that he regards respect for tradition and concepts of the sacred as valuable in and of themselves, as means of social control, regardless of their intrinsic value. In Tempting, Bork acknowledges that some things are part of "the traditions of our people" without being very worthy. In Gomorrah, he seems to believe that all institutions and traditions must be upheld, simply because they are established and traditional.

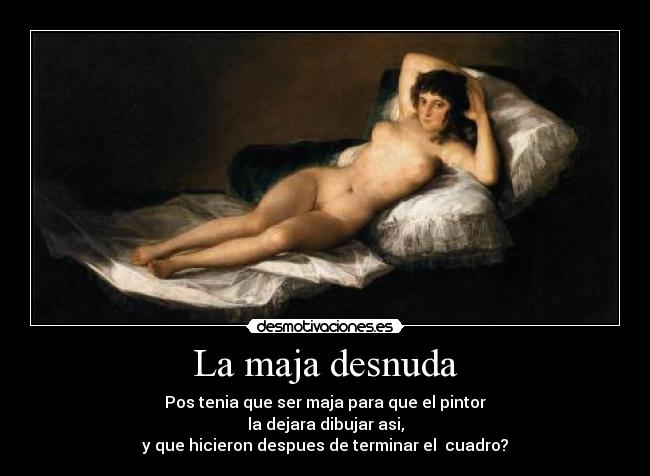

Bork sees as signs of our social decline Catholics who question the will of the Pope instead of automatically obeying, Protestants who question the inerrancy of the Bible for no better reason than that it is contradicted by physical evidence, oh yes, and the decline (in our universities) of "the critical, scientific spirit." As evidence that political correctness is ruining the culture of our universities, Bork give the example of a non-art class being taught in an art classroom with a copy of Goya's Maja Desnuda on the wall. When some male students in the class snickered at the nude, the professor asked the administration to take it down. (When asked about the incident, she said that the painting did not offend her, she only wanted it removed because it was creating a disturbance). I leave to the imagination what the response would have been, and whether Bork would have approved if the Maja Desnuda had appeared in any high school art room.

In fact, at the time Bork wrote, many trends were underway that he would presumably have seen as favorable. Income distribution was becoming less equal, taxes were becoming less progressive, and rates of incarceration were rising. But none of these counted for Bork because some people criticized them, and only if these trends had been greeted with universal acclaim would they have been signs of moral health. Also revealing is what Bork did not see as cultural decay. Drug gangs shooting it out in our inner cities was a sign of cultural decay. Firearms manufacturers openly marketing a produced under the name of Streetsweeper was not, and neither was the presence of armed militias running training camps dedicated to the overthrow of the federal government. Black people believing mad conspiracy theories about the CIA trafficking drugs and inventing AIDS was a sign of social decay. White people believing mad conspiracy theories about black helicopters, UN takeovers, or Elvis being alive was not. Movies promoting senseless sex and violence was a sign of social decay. Talk radio spewing hate and vitriol, including G. Gordon Liddy giving advice on how to kill federal agents, was not. In fact, the bare fact that talk radio offended liberals was proof enough to Bork that it must be good. In his denunciations of political correctness, Bork points out how easy it was to dismiss any evidence contrary to the theory as counter revolutionary props of the status quo. Little did he suspect that in the coming years his conservatives would adopt the technique on a much larger and more powerful scale, dismissing any embarrassing contrary evidence as mere "liberal bias."

Of course, one can fairly ask whether this is the result of bitterness as a result of losing the nomination. Perhaps if Bork had been confirmed to the Supreme Court, he would have retained the relative sanity of his earlier work. However, the intemperate paranoia of Bork's later work is more than ample to convince me that I am really glad he was not confirmed for the Supreme Court.

________________________________________________________________________

*In particular, Bork, although a supporter of states' rights, is extremely critical of Jefferson for taking states' rights to extremes that he considers threatening to the survival of the union. He admires John Marshall, but is critical of many of his opinions.

**It should also be noted that Bork acknowledges that the left has largely abandoned its interest in economic issues and ceded that territory to the right. He fails to acknowledge the obvious however -- that this represents a huge victory for his side.

Sunday, December 23, 2012

Reflections on Robert Bork

Saturday, November 24, 2012

So, with all that out of the way, do I seriously believe that today's Republicans have become pre-Enlightenment conservatives in today's fast-paced society?

Obviously Republicans are not all the same. At the far extreme are Glenn Beck and his fans, and the ones who march in 18th Century costumes and call for a return to the Founding Fathers. Let us make no mistake what they think they are talking about. They regard the Constitution as a document straight from God, believe that the Founding Fathers had established the ideal and perfect social order, and that and variation from the ideal social order they had founded can only be degeneration. In other words, society should be frozen in amber, even as technology changes, and being true to the vision of the Founders means re-creating an 18th Century society with present-day technology. This is the very essence of pre-Enlightenment conservatism.

Admittedly, these pre-Enlightenment conservatives are willing to admit that there was trouble in paradise in the form of the little matter of slavery. The Glenn Beck/18th Century costumes wing of movement conservatism does acknowledge that slavery was a blemish on our society at the founding, and that to be ideal it would have to change in that one regard. But they take a decidedly modern conservative approach to ending slavery. Active agitation against slavery just makes slave holders dig in their heels; the only acceptable way for slavery to end is for it to die out on its own. And they regard an 18th Century society, minus slavery and with modern day technology, as the ideal society that must be held in stasis and never allowed to change (except in technology).

Of course, this crowd does not know much about what the 18th Century social order was really like. They simply take their ideas of libertarianism and minimal government and assume that it was what existed when this country was founded. They are wrong. I confess I have only glanced at, not read The Radicalism of the American Revolution, and I do not know enough about the history of the era to know to what extent I should accept its thesis. But I have seen enough to recognize that the book describes what the 18th Century social order looked like and why it was far from any sort of modern libertarianism, or, indeed, anything modern-day American, anywhere across the political spectrum would want to duplicate. It was a society that did not truly have the concept of the state being separate from society, and certainly a social order incompatible with anything like modern industrial capitalism. He further argues that the full transformation did not end with the Revolution, but only truly came to fruition in the early 19th Century.

All of which leads me to an inescapable conclusion. The Beck wing of the conservative movement may say it wants a return to the Founding Era and the society and values of the 1780's. But what they are actually seeking to create looks a lot more like the 1880's -- the Gilded Age. Beck himself more or less gives himself away in his choice of villains. Glenn Beck famously hates Progressivism. His favorite villain is Woodrow Wilson, but he believes the decline really began with Teddy Roosevelt. And who were these Progressives, Wilson and Roosevelt included? They were the people who opposed the worst excesses of the Gilded Age. They did not favor ending industrial capitalism by any means, but they favored curbing its abuses through anti-trust legislation, labor and consumer protection, workers' compensation, anti-trust legislation, regulation, limiting big money in politics and so forth. If the people who sought reforms to end the Gilded Age are Beck's villains, what are we to conclude, if not that the Gilded Age is the ideal society that he favors?

As for more mainstream movement conservatives, my guess is that most of them also basically regard the Gilded Age as our golden age and would like to get back to it. But they also understand that such a project is not politically feasible. But if they do not openly express a desire to return to the 1780's or the 1880's, plenty of mainstream Republicans are unwilling to budge from the 1980's. When confronted with the suggestion that things have changed since the 1980's and that perhaps they should change their program to adapt, they respond that conservatism stands for universal the timeless principles and therefore does not have to change its program.

The timeless truths embodied in their program are that we should cut taxes and gut regulations. Pointing out that a top marginal rate of 70% and a top marginal rate or 36% may not be the same thing, or that government once regulated the route and fare of every truck, train, plane and ship in the country, makes no difference. These are distinctions for people who accept the moral legitimacy of taxes and regulations, and believe that they are best determined by social utility. If, on the other hand, you believe as a universal and timeless principle that all taxes and regulations are morally illegitimate, but recognize that eliminating them altogether is not practical, then it is a universal and timeless truth that taxes are always too high, regulations are always stifling, and that a crusade to cut taxes and gut regulations is always a moral imperative.

Though it gets less attention, some of the same consideration applies to monetary policy. Conservatives often praise Paul Volcker, Ronald Reagan's chairman of the Federal Reserve for tightening monetary policy, no matter how painful. They seem to take an almost prurient delight in the pain he inflicted -- skyrocketing interest rates, a severe recession, farmers bankrupted, Latin American thrown into economic crisis -- and urge today's Fed to do the same thing. Why, one might ask? Volcker was willing to inflict so much pain to break an inflationary spiral that had reached 14%. Given that we don't have an inflationary spiral right now, and that there is a severe recession going on and an international economic crisis despite the Fed's monetary expansion to soften the blow, why should we want to make things even worse? The usual answer we get is fear of inflation. But just how much pain do we have to inflict, not just on ourselves, but the rest of the world, in the interest of fighting an inflation that hasn't even shown up?

It makes more sense if you don't think of monetary policy as a means of achieving an economic end, but as a sort of moral imperative. Monetary expansion, or, as it is called, loose money, is a sign of moral laxness. Tight money means moral rectitude. And if you think of these as universal and timeless moral principles -- that taxation and regulation are morally illegitimate, that tight money is always a moral imperative -- then there is no need to change policies to adjust to changing circumstances. Ronald Reagan's policy prescriptions are not just responses to certain economic circumstances, but universal and timeless truths that must always be followed. And this really is moving in the direction of treating public policy as a branch of theology.

Obviously Republicans are not all the same. At the far extreme are Glenn Beck and his fans, and the ones who march in 18th Century costumes and call for a return to the Founding Fathers. Let us make no mistake what they think they are talking about. They regard the Constitution as a document straight from God, believe that the Founding Fathers had established the ideal and perfect social order, and that and variation from the ideal social order they had founded can only be degeneration. In other words, society should be frozen in amber, even as technology changes, and being true to the vision of the Founders means re-creating an 18th Century society with present-day technology. This is the very essence of pre-Enlightenment conservatism.

Admittedly, these pre-Enlightenment conservatives are willing to admit that there was trouble in paradise in the form of the little matter of slavery. The Glenn Beck/18th Century costumes wing of movement conservatism does acknowledge that slavery was a blemish on our society at the founding, and that to be ideal it would have to change in that one regard. But they take a decidedly modern conservative approach to ending slavery. Active agitation against slavery just makes slave holders dig in their heels; the only acceptable way for slavery to end is for it to die out on its own. And they regard an 18th Century society, minus slavery and with modern day technology, as the ideal society that must be held in stasis and never allowed to change (except in technology).

Of course, this crowd does not know much about what the 18th Century social order was really like. They simply take their ideas of libertarianism and minimal government and assume that it was what existed when this country was founded. They are wrong. I confess I have only glanced at, not read The Radicalism of the American Revolution, and I do not know enough about the history of the era to know to what extent I should accept its thesis. But I have seen enough to recognize that the book describes what the 18th Century social order looked like and why it was far from any sort of modern libertarianism, or, indeed, anything modern-day American, anywhere across the political spectrum would want to duplicate. It was a society that did not truly have the concept of the state being separate from society, and certainly a social order incompatible with anything like modern industrial capitalism. He further argues that the full transformation did not end with the Revolution, but only truly came to fruition in the early 19th Century.

All of which leads me to an inescapable conclusion. The Beck wing of the conservative movement may say it wants a return to the Founding Era and the society and values of the 1780's. But what they are actually seeking to create looks a lot more like the 1880's -- the Gilded Age. Beck himself more or less gives himself away in his choice of villains. Glenn Beck famously hates Progressivism. His favorite villain is Woodrow Wilson, but he believes the decline really began with Teddy Roosevelt. And who were these Progressives, Wilson and Roosevelt included? They were the people who opposed the worst excesses of the Gilded Age. They did not favor ending industrial capitalism by any means, but they favored curbing its abuses through anti-trust legislation, labor and consumer protection, workers' compensation, anti-trust legislation, regulation, limiting big money in politics and so forth. If the people who sought reforms to end the Gilded Age are Beck's villains, what are we to conclude, if not that the Gilded Age is the ideal society that he favors?

As for more mainstream movement conservatives, my guess is that most of them also basically regard the Gilded Age as our golden age and would like to get back to it. But they also understand that such a project is not politically feasible. But if they do not openly express a desire to return to the 1780's or the 1880's, plenty of mainstream Republicans are unwilling to budge from the 1980's. When confronted with the suggestion that things have changed since the 1980's and that perhaps they should change their program to adapt, they respond that conservatism stands for universal the timeless principles and therefore does not have to change its program.

The timeless truths embodied in their program are that we should cut taxes and gut regulations. Pointing out that a top marginal rate of 70% and a top marginal rate or 36% may not be the same thing, or that government once regulated the route and fare of every truck, train, plane and ship in the country, makes no difference. These are distinctions for people who accept the moral legitimacy of taxes and regulations, and believe that they are best determined by social utility. If, on the other hand, you believe as a universal and timeless principle that all taxes and regulations are morally illegitimate, but recognize that eliminating them altogether is not practical, then it is a universal and timeless truth that taxes are always too high, regulations are always stifling, and that a crusade to cut taxes and gut regulations is always a moral imperative.

Though it gets less attention, some of the same consideration applies to monetary policy. Conservatives often praise Paul Volcker, Ronald Reagan's chairman of the Federal Reserve for tightening monetary policy, no matter how painful. They seem to take an almost prurient delight in the pain he inflicted -- skyrocketing interest rates, a severe recession, farmers bankrupted, Latin American thrown into economic crisis -- and urge today's Fed to do the same thing. Why, one might ask? Volcker was willing to inflict so much pain to break an inflationary spiral that had reached 14%. Given that we don't have an inflationary spiral right now, and that there is a severe recession going on and an international economic crisis despite the Fed's monetary expansion to soften the blow, why should we want to make things even worse? The usual answer we get is fear of inflation. But just how much pain do we have to inflict, not just on ourselves, but the rest of the world, in the interest of fighting an inflation that hasn't even shown up?

It makes more sense if you don't think of monetary policy as a means of achieving an economic end, but as a sort of moral imperative. Monetary expansion, or, as it is called, loose money, is a sign of moral laxness. Tight money means moral rectitude. And if you think of these as universal and timeless moral principles -- that taxation and regulation are morally illegitimate, that tight money is always a moral imperative -- then there is no need to change policies to adjust to changing circumstances. Ronald Reagan's policy prescriptions are not just responses to certain economic circumstances, but universal and timeless truths that must always be followed. And this really is moving in the direction of treating public policy as a branch of theology.

Friday, November 23, 2012

Modern Conservatism

So, what is modern conservatism? I will start with two comments. One is that I am no scholar of modern conservatism. I have not read Edmund Burke, Friedrich Hayek, Russell Kirk, or other conservative philosophers. But secondly, I do not think being a scholar of modern conservatism is necessary to comment present day right wing politics. Few of our politicians are scholars of any ideology and few still (proportionately) of the voting public. I do not believe, therefore, that any more than the crudest approximation of modern conservative ideology is necessary to discuss practical politics.

With that out of the way, I would define modern conservatism in comparison and contrast to pre-Enlightenment conservatism.

Modern conservatism is secular:

Modern conservatives individually may be either believers or non-believers. Even the non-believers may encourage religion as necessary to promote good behavior. But modern conservatives do not believe that God has decreed any one social order. Modern conservatism began as a critique of classical liberalism, but it has adopted at least one classical liberal premise -- "Because God said so" is not a sufficient argument. When modern conservatives want to argue for a particular institution, policy or tradition, they make their argument in secular terms.

Modern conservatism upholds the status quo:

Generally speaking, modern conservatism rejects not only revolution, but reform as illegitimate. Social engineering is a dirty word to modern conservatives, while the Law of Unintended Consequences is almost sacred. Modern conservatives do not see society as a static unit ordained by God, but they do see it as the product of a long process of development, a set of organic traditions, a spontaneous order, the workings of the free market, or similarly complicated process. What they do not see society as is a rational construct that is the product of conscious decisions by individual social planners. Or, put differently, God did not say, "Let there be a specific social order," and neither did any human actor. The social order, in one form or another, is seen as a complex, fragile, tightly interdependent whole. Tampering with any part of it may have unforeseen and possible devastating consequences to other, far-flung parts of the whole.

At the same time, modern conservatism recognizes the necessity and inevitability of change:

While modern conservatives distrust all reforms as "liberal social engineering," they also realize that change is inevitable, and that any attempt to freeze society in amber is itself a form of social engineering. Modern conservatives are therefore most accepting of change if it happens on its own without anyone specifically intending it. The proper mechanism depends on the branch of modern conservatism. Perhaps an organic tradition may develop slowly or a spontaneous order emerge on its own. To a libertarian, a mass of atomized actors may all individually decide they want something new and convey that change through the mechanism of the market. Or a brilliant entrepreneur may come up with a new invention that has far-ranging social consequences. For instance, when Henry Ford invented the assembly line and changed cars from a rich man's luxury to a product available to the general public, this invention had far-ranging consequences. It broke the power of the railroad companies which once had such a stranglehold on commerce and travel. Making travel much faster from any point to any other had complex effects on residential density. And (rumor has it) easy access to cars worked a loosening of sexual mores. But Henry Ford did not intend any of these far-ranging social effects; he was just making cars.

All of this illustrates an obvious reason why pre-Enlightenment conservatism is no longer viable in the modern age. Before the Industrial Revolution, one might realistically fantasize about a static, unchanging society. Since the Industrial Revolution, it has become obvious the technological change is with us to stay. And to expect technological change not to bring about social change is simply unrealistic. And yet some Republicans are doing just that these days. That will be the subject of my next post.

With that out of the way, I would define modern conservatism in comparison and contrast to pre-Enlightenment conservatism.

Modern conservatism is secular:

Modern conservatives individually may be either believers or non-believers. Even the non-believers may encourage religion as necessary to promote good behavior. But modern conservatives do not believe that God has decreed any one social order. Modern conservatism began as a critique of classical liberalism, but it has adopted at least one classical liberal premise -- "Because God said so" is not a sufficient argument. When modern conservatives want to argue for a particular institution, policy or tradition, they make their argument in secular terms.

Modern conservatism upholds the status quo:

Generally speaking, modern conservatism rejects not only revolution, but reform as illegitimate. Social engineering is a dirty word to modern conservatives, while the Law of Unintended Consequences is almost sacred. Modern conservatives do not see society as a static unit ordained by God, but they do see it as the product of a long process of development, a set of organic traditions, a spontaneous order, the workings of the free market, or similarly complicated process. What they do not see society as is a rational construct that is the product of conscious decisions by individual social planners. Or, put differently, God did not say, "Let there be a specific social order," and neither did any human actor. The social order, in one form or another, is seen as a complex, fragile, tightly interdependent whole. Tampering with any part of it may have unforeseen and possible devastating consequences to other, far-flung parts of the whole.

At the same time, modern conservatism recognizes the necessity and inevitability of change:

While modern conservatives distrust all reforms as "liberal social engineering," they also realize that change is inevitable, and that any attempt to freeze society in amber is itself a form of social engineering. Modern conservatives are therefore most accepting of change if it happens on its own without anyone specifically intending it. The proper mechanism depends on the branch of modern conservatism. Perhaps an organic tradition may develop slowly or a spontaneous order emerge on its own. To a libertarian, a mass of atomized actors may all individually decide they want something new and convey that change through the mechanism of the market. Or a brilliant entrepreneur may come up with a new invention that has far-ranging social consequences. For instance, when Henry Ford invented the assembly line and changed cars from a rich man's luxury to a product available to the general public, this invention had far-ranging consequences. It broke the power of the railroad companies which once had such a stranglehold on commerce and travel. Making travel much faster from any point to any other had complex effects on residential density. And (rumor has it) easy access to cars worked a loosening of sexual mores. But Henry Ford did not intend any of these far-ranging social effects; he was just making cars.

All of this illustrates an obvious reason why pre-Enlightenment conservatism is no longer viable in the modern age. Before the Industrial Revolution, one might realistically fantasize about a static, unchanging society. Since the Industrial Revolution, it has become obvious the technological change is with us to stay. And to expect technological change not to bring about social change is simply unrealistic. And yet some Republicans are doing just that these days. That will be the subject of my next post.

Pre-Enlightenment Conservatism

Conservatism in its modern form is a relatively recent phenomenon, generally attributed to Edmund Burke. But conservatism in the sense of upholding the status quo of power is presumably as old as status quos of power that require upholding. But older forms of conservatism -- what I can pre-Enlightenment conservatism -- have certain traits that are really not viable in any modern society.

To offer a concrete example, let me express gratitude to Albion's Seed for its description of the Puritans as excellent examples of reformist-to-revolutionary pre-Enlightenment conservatives. The Puritans certainly offered many radical challenges to the contemporary English social order. They challenged primogeniture (the rule that all family land goes to the oldest son), entailment (limiting land to a particular family), escheat (the rule that if the owner of land dies without an heir, all land reverts to his feudal lord) and various taxes and burdens on inheritance. They called the English family into question, permitting divorce if the conditions of a marriage were not kept, forbidding husbands from beating their wives, and protecting wives, children, servants and slaves from the "unnatural severity" of the head of household. They challenged the authority of the king and nobility, built a society with no hereditary aristocracy, and built a government in New England in which authority rested on election by the people. In England, what began as a movement seeking reforms to "purify" the church and state ended up becoming a revolution which overthrew the monarchy and beheaded the King for treason almost 150 years before the French made such things fashionable.

To offer a concrete example, let me express gratitude to Albion's Seed for its description of the Puritans as excellent examples of reformist-to-revolutionary pre-Enlightenment conservatives. The Puritans certainly offered many radical challenges to the contemporary English social order. They challenged primogeniture (the rule that all family land goes to the oldest son), entailment (limiting land to a particular family), escheat (the rule that if the owner of land dies without an heir, all land reverts to his feudal lord) and various taxes and burdens on inheritance. They called the English family into question, permitting divorce if the conditions of a marriage were not kept, forbidding husbands from beating their wives, and protecting wives, children, servants and slaves from the "unnatural severity" of the head of household. They challenged the authority of the king and nobility, built a society with no hereditary aristocracy, and built a government in New England in which authority rested on election by the people. In England, what began as a movement seeking reforms to "purify" the church and state ended up becoming a revolution which overthrew the monarchy and beheaded the King for treason almost 150 years before the French made such things fashionable.

Yet the Puritans were also pre-Enlightenment conservatives in the sense that they believed that there was only one right social order, ordained by God, and that once a proper Christian commonwealth was established any change was degeneration and deviation from God's will. "New," "novelty" and "innovation" were all used as perjoratives, to indicate falling from the Truth. "Change of any sort seemed to be cultural disintegration."* If the Puritans were not conservative about contemporary England, they were conservative in believing in perfection, not progress, that God intended one social order and only one, and that no changes were to be tolerated.

By contrast, the Royalists who colonized Virginia were conservative to reactionary pre-Enlightenment conservatives. Initially, they were conservative conservatives, seeking to uphold the status quo in contemporary England from Puritan challenge. When the Puritans seized power in England, Royalists migrated in large numbers to Virginia, now as reactionary conservatives, seeking to re-create the social order as it had existed in England before the Puritans came to power. Either way, they, too, saw "new," "novelty," "innovation" and "modern" as perjoratives and any change as disastrous.

It was in the late 17th Century that the early stirrings of the Enlightenment began and a radical new ideology arose -- the ideology of classical liberalism. This bold new ideology denied that God intended any particular social order. God gave people individual rights, no more. The social order was no more than a set of institutions rationally created by the people to safeguard their individual rights. If at some future time, the people decided that other institutions or a different social order would safeguard their rights better, they were free to make changes, or even to overthrow the whole system. This new ideology of classical liberalism was brought to America by Quakers in the later 17th Century. It was adopted by the Virginia Royalists. It was widely held on both sides of the Atlantic throughout the 18th Century. It was the ideology of the American Revolution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution.

Classical liberalism was also the ideology of the French Revolution, where it proved to be capable of dangerous excesses. When all social institutions are regarded as optional, as artificial constructs that can be cast aside when they are no longer rationally seen as useful, it turned out that serious social breakdown and upheaval can ensue when someone takes this ideology too seriously. It was in response to this danger that modern conservatism arose. Modern conservatism was a reaction against classical liberalism, but also influenced by it.

It will be the subject of my next post.

_______________________________________________

*Albion's Seed, page 56.

Pre-Enlightenment conservatism assumes a social order decreed by God:

This is what I mean by politics or policy as theology. Such an outlook treats any challenge to God's ordained social order as a challenge to God Himself. The danger of such an outlook to democratic politics, or any sort of normal politics, should be obviousl

Pre-Enlightenment conservatism calls for social stasis:

As we say in twelve-step organizations, progress, not perfection. Indeed, progress and perfection are essentially incompatible. Consider: progress means improvement; perfection means there is no room for improvement. To anyone who believes that a certain social order is decreed by God, that social order is presumably not perfect because it is made up of flawed and sinful individuals. But if all people followed their proper roles, has God intended, then such a society is as perfect as anything that can be achieved in this sinful world, and any change in the social order will necessarily be for the worse. The most anyone intent on improving society can do is denounce people's individual sins and call on them to live up to the proper (social) roles God intended for them. But any sort of reform -- not just in an attempt to improve society, but even to adjust to changing conditions -- is degeneration and, indeed, blasphemy.

Pre-Enlightenment conservatism can be conservative, reactionary, revolutionary, and perhaps even reformist, but never liberal or progressive:

An important qualification is in order here. Pre-Enlightenment conservatives are all conservative in the sense of believing that there is a certain social order that must be conserved against all change. But they are not necessarily conservative in the sense of believing that that order is the social order as it exists today. Certainly a pre-Enlightenment conservative can be conservative in the sense of defending the current status quo of power, and than any flaws are simply the result of individual sin. Conservatives of this type are most likely to arise when the current social order is being challenged, in order to uphold it against challenges. Alternately, pre-Enlightenment conservatism may be reactionary, seeking to return to a social order of the (recent and remembered) past. From this perspective, the true, proper social order ordained by God existed until recently, and present-day society is acting in defiance of it. This type of conservatism is most likely to occur when society has undergone recent, disruptive changes and many people long for a recent past before the changes happened. But sometimes pre-Enlightenment conservatism takes a more radical view -- perhaps reformist, perhaps revolutionary, perhaps even millenarian. Such a viewpoint sees society as radically out of synch with the social order that God intended, and in need of major changes to bring it into conformity with God's will.

What pre-Enlightenment conservative can never be is liberal or progressive because these are ideologies that embrace continual change and improvement.

What pre-Enlightenment conservative can never be is liberal or progressive because these are ideologies that embrace continual change and improvement.

To offer a concrete example, let me express gratitude to Albion's Seed for its description of the Puritans as excellent examples of reformist-to-revolutionary pre-Enlightenment conservatives. The Puritans certainly offered many radical challenges to the contemporary English social order. They challenged primogeniture (the rule that all family land goes to the oldest son), entailment (limiting land to a particular family), escheat (the rule that if the owner of land dies without an heir, all land reverts to his feudal lord) and various taxes and burdens on inheritance. They called the English family into question, permitting divorce if the conditions of a marriage were not kept, forbidding husbands from beating their wives, and protecting wives, children, servants and slaves from the "unnatural severity" of the head of household. They challenged the authority of the king and nobility, built a society with no hereditary aristocracy, and built a government in New England in which authority rested on election by the people. In England, what began as a movement seeking reforms to "purify" the church and state ended up becoming a revolution which overthrew the monarchy and beheaded the King for treason almost 150 years before the French made such things fashionable.

To offer a concrete example, let me express gratitude to Albion's Seed for its description of the Puritans as excellent examples of reformist-to-revolutionary pre-Enlightenment conservatives. The Puritans certainly offered many radical challenges to the contemporary English social order. They challenged primogeniture (the rule that all family land goes to the oldest son), entailment (limiting land to a particular family), escheat (the rule that if the owner of land dies without an heir, all land reverts to his feudal lord) and various taxes and burdens on inheritance. They called the English family into question, permitting divorce if the conditions of a marriage were not kept, forbidding husbands from beating their wives, and protecting wives, children, servants and slaves from the "unnatural severity" of the head of household. They challenged the authority of the king and nobility, built a society with no hereditary aristocracy, and built a government in New England in which authority rested on election by the people. In England, what began as a movement seeking reforms to "purify" the church and state ended up becoming a revolution which overthrew the monarchy and beheaded the King for treason almost 150 years before the French made such things fashionable. Yet the Puritans were also pre-Enlightenment conservatives in the sense that they believed that there was only one right social order, ordained by God, and that once a proper Christian commonwealth was established any change was degeneration and deviation from God's will. "New," "novelty" and "innovation" were all used as perjoratives, to indicate falling from the Truth. "Change of any sort seemed to be cultural disintegration."* If the Puritans were not conservative about contemporary England, they were conservative in believing in perfection, not progress, that God intended one social order and only one, and that no changes were to be tolerated.

By contrast, the Royalists who colonized Virginia were conservative to reactionary pre-Enlightenment conservatives. Initially, they were conservative conservatives, seeking to uphold the status quo in contemporary England from Puritan challenge. When the Puritans seized power in England, Royalists migrated in large numbers to Virginia, now as reactionary conservatives, seeking to re-create the social order as it had existed in England before the Puritans came to power. Either way, they, too, saw "new," "novelty," "innovation" and "modern" as perjoratives and any change as disastrous.

It was in the late 17th Century that the early stirrings of the Enlightenment began and a radical new ideology arose -- the ideology of classical liberalism. This bold new ideology denied that God intended any particular social order. God gave people individual rights, no more. The social order was no more than a set of institutions rationally created by the people to safeguard their individual rights. If at some future time, the people decided that other institutions or a different social order would safeguard their rights better, they were free to make changes, or even to overthrow the whole system. This new ideology of classical liberalism was brought to America by Quakers in the later 17th Century. It was adopted by the Virginia Royalists. It was widely held on both sides of the Atlantic throughout the 18th Century. It was the ideology of the American Revolution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution.

Classical liberalism was also the ideology of the French Revolution, where it proved to be capable of dangerous excesses. When all social institutions are regarded as optional, as artificial constructs that can be cast aside when they are no longer rationally seen as useful, it turned out that serious social breakdown and upheaval can ensue when someone takes this ideology too seriously. It was in response to this danger that modern conservatism arose. Modern conservatism was a reaction against classical liberalism, but also influenced by it.

It will be the subject of my next post.

_______________________________________________

*Albion's Seed, page 56.

The Republican Party and Politics as Theology

If I were to attempt to define what went wrong with the Republican Party, it would be that they abandoned modern conservatism in favor of pre-Enlightenment conservatism and began treating politics and policy as a branch of theology. I do not know what will restore the fortunes of the Republican Party. But I know that until they stop treating politics as a branch of theology and embrace modern conservatism, health will not return to our democracy.

Needless to say, after making such a statement, it is only right that I define my terms.

POLITICS/POLICY AS THEOLOGY:

Theology technically means the study of God. But in fact, theology covers more than seeking to understand the nature of God. It also means seeking to understand God's will, particularly God's will for us humans, and how we should obey God's will. This what is known as moral theology, or Christian ethics. It faces the constant difficulty of distinguishing between what is actually God's will (or a serious moral issue) and what is mere social convention. C.S. Lewis addresses this issue beautifully on the subject of sexual ethics. All Christians in all societies, he argues, should dress modestly and not provocatively, and may be straightforward in their speech, but not prurient. But how to tell modest from immodest dress, or direct from prurient speech, is extremely culture-bound. His advice is to follow the accepted mores of one's culture, regardless of what they are. This can be particularly difficult when they are rapidly changing. In that case, he recommends assuming the best about others so long as such an assumption is sustainable. If Lewis were to look at the Religious Right today, he would presumably agree with them in condemning sex outside of marriage, and regarding homosexuality as a perversion. But he would disagree that these goals can be achieved only by specific social conventions.

But if discerning God's will in individual conduct is difficult and dangerous, in politics and public policy it is vastly more so. Again, any religious conservative would do well to heed C.S. Lewis on this. Christianity does not endorse any particular political program, nor are the clergy the best specialists in coming up with one. His own proposal for what a Christian society would look like would be one in which everyone worked for a living, making something useful, and there was no conspicuous consumption or status goods. It would be hierarchical, with everyone obeying and deferring to their natural superiors. And it would be joyful, rejecting worry or anxiety. One can argue with him on any of these, but his basic point -- that Christian social policy is about general goals of what society should look like, no any particular concrete step to achieve them -- is sound. Too often, today's religious conservatives assume that certain policies -- or worse, certain politicians -- are either wholly good or wholly evil, either the work of God or the Devil. This leaves no room for the normal business of politics -- negotiation and compromise, often on matters of little or no intrinsic moral significance.

It is the assumption that God intends a certain social order or, worse, specific policies or politicians, that is what I mean by treating politics or policy as a branch of theology.

Next: Pre-Enlightenment Conservatism

Needless to say, after making such a statement, it is only right that I define my terms.

POLITICS/POLICY AS THEOLOGY:

Theology technically means the study of God. But in fact, theology covers more than seeking to understand the nature of God. It also means seeking to understand God's will, particularly God's will for us humans, and how we should obey God's will. This what is known as moral theology, or Christian ethics. It faces the constant difficulty of distinguishing between what is actually God's will (or a serious moral issue) and what is mere social convention. C.S. Lewis addresses this issue beautifully on the subject of sexual ethics. All Christians in all societies, he argues, should dress modestly and not provocatively, and may be straightforward in their speech, but not prurient. But how to tell modest from immodest dress, or direct from prurient speech, is extremely culture-bound. His advice is to follow the accepted mores of one's culture, regardless of what they are. This can be particularly difficult when they are rapidly changing. In that case, he recommends assuming the best about others so long as such an assumption is sustainable. If Lewis were to look at the Religious Right today, he would presumably agree with them in condemning sex outside of marriage, and regarding homosexuality as a perversion. But he would disagree that these goals can be achieved only by specific social conventions.

But if discerning God's will in individual conduct is difficult and dangerous, in politics and public policy it is vastly more so. Again, any religious conservative would do well to heed C.S. Lewis on this. Christianity does not endorse any particular political program, nor are the clergy the best specialists in coming up with one. His own proposal for what a Christian society would look like would be one in which everyone worked for a living, making something useful, and there was no conspicuous consumption or status goods. It would be hierarchical, with everyone obeying and deferring to their natural superiors. And it would be joyful, rejecting worry or anxiety. One can argue with him on any of these, but his basic point -- that Christian social policy is about general goals of what society should look like, no any particular concrete step to achieve them -- is sound. Too often, today's religious conservatives assume that certain policies -- or worse, certain politicians -- are either wholly good or wholly evil, either the work of God or the Devil. This leaves no room for the normal business of politics -- negotiation and compromise, often on matters of little or no intrinsic moral significance.

It is the assumption that God intends a certain social order or, worse, specific policies or politicians, that is what I mean by treating politics or policy as a branch of theology.

Next: Pre-Enlightenment Conservatism

Sunday, November 18, 2012

False Memory, pp. 466-540 (with intervals)

So, as I suggested in my last post on the subject, I omitted the Ahriman parts because they deserve their own section. Up till now Koontz's portrayal of Ahriman has been mostly annoying. Certainly we need some scenes from Ahriman's perspective to explain how his brainwashing works and what he is up to. Koontz does this to some extent, but ultimately leaves a lot of clues dangling and unexplained. Instead, he wastes a lot of precious time and energy showcasing how evil Ahriman is. Apparently exercising mind control over patients, implanting phobias to torment them, raping female patients and subjecting them to unspeakable depravities, and driving some patients to suicide and spectacular just isn't evil enough for Koontz. He has to flash back to Ahriman's past and show him killing both parents, burning down their houses to cover the evidence, dissecting live animals, and so forth. He also makes him part of a sinister plot to take over the world.

The sinister plot to take over the world does have one advantage, though. It means that Ahriman is no longer the puppet master in control of everything, in fact, he is no longer any more than a bit player. And with Ahriman no longer in control, he can be used for comic relief. There is always an obvious risk in the comic villain, of course. Laughter is generally incompatible with either hate or fear, so a comic villain tends not to be so menacing or so truly evil as a serious one. But then again, Ahriman has already established his evil to everyone's satisfaction, and seeing the puppet master lose control can be the best revenge. This is the first time reading about Ahriman has actually been fun, so let us savor it for a change.

Ahriman has a new patient with a most creative and original phobia that Ahriman had no role in creating. She is the wife of one of those entrepreneurs who were rampant in the 1990's who made a half billion dollar fortune sellingdesigner toilet paper internet stock. She was was once a huge Keanu Reeves fan, but has now developed an uncontrollable fear of him.

Interestingly to note, her name is never given. She is simply referred to as the Keanuphobe or, later, when our heroes see her in a pink suit, as the pink lady. Her lack of a name is striking. Normally, Koontz gives even very minor characters names. For instance, all personnel at the New Life Clinic have names. The nurses who attend Skeet, the doctor on call, the security guard who makes a total of two short appearances, and even the head nurse, whose single appearance takes a single page, has a name. The lab tech who draws Martie's blood for testing has a name. The police who respond to Susan's suicide have names. A few waiters, sales people, and the security guard in the gated community where Skeet attempts suicide do not have names, and that makes sense. They are seen only from the perspective of Dusty (or Ahriman). Since the person seeing them does not know their name, it is not given. Thus far the only other character whose name is known to a POV (point of view) character whose name is not given is the unnamed Famous Actor who Ahriman programs to bite the President's nose off. Koontz unwillingness to name the Famous Actor (other than to say he is not Keanu Reeve) is understandable. It he actually identified a real famous actor, calling him a drug addict and as stupid as the character is portrayed, he might get in trouble with the actor's lawyers. And if he made up a name, people would complain that for such a famous actor, they have never heard of him. But in any case, Famous Actor is a minor character. We lose very little by not knowing his name. The Keanuphobe (as we shall see) plays a major, indeed, critical, role in the story. Are Internet con men so famous that Koontz couldn't make up a name for one and his wife?

In any event, while shopping and eating lunch, Ahriman notices a red-faced man driving a beat-up old camper truck seems to be watching him. Furthermore, wherever he drives, the beat-up truck follows. The man's name is not given because Ahriman does not know it. But we do. The truck has two very strange antennae on it, and the red-faced man has a passenger -- Skeet. Ahriman has his manservant take his other car to the parking lot next door. He then has his secretary, Jennifer, drive his car to the dealership for maintenance and trails the two men trailing him. Once Jennifer drops off the car, she takes off walking because she is a health and fitness nut. Skeet and Fig follow her. Comic scenes ensue. Ahriman knows that, as a health and fitness nut, Jennifer will eat at Green Acres, a health food restaurant. His own tastes run more to sweets, as unhealthy as possible, so we get an entertaining scene of him looking around the counter for something he would be willing to eat. There are actually some chocolate coconut bars "no butter, margarine, or hydrogenated vegetable shortening," but he takes them anyhow, at a discount because the hostess is so relieved to be rid of them. He also makes comical observations about Skeet and Fig's poor surveillance technique and increasingly starts thinking of Jennifer as a horse, given her taste in food. He wonders if Skeet and Fig are gay lovers, and if he could endure the sight of them in action while shooting them. And he notices a white Rolls Royce at Green Acres and wonders how anyone with the wealth and taste to drive such a car could eat at such a place. (Any guesses what unnamed character that is?).

Fig and Skeet follow Jennifer home and are followed by Ahriman. When she goes in and nothing further happens, they take the dog out, let him poop, and then collect it in a blue bag and throw it in the trash. Ahriman retrieves it, not knowing yet what he intends to do with it. (This, too, will be significant and comical). He trails Fig and Skeet to the beach. They wade out into the ocean with their electronic gear, trying to contact UFO's. Ahriman is baffled, but doesn't have time to figure it out. Instead, he shoots them in the chest. "Your mother's a whore, your father's a fraud, and your stepfather's got pig shit for brains," says Ahriman to Skeet. And this, on page 527, is our first hint that this particular family may be more than random victims to Ahriman. Just as he is about to shoot the dog, he notices that it is barking at someone behind him. He turns around and sees the unnamed Keanuphobe. Yes, the white Rolls Royce was hers, and while Fig and Skeet were following Jennifer and Ahriman was following Fig and Skeet, the Keanuphobe was following Ahriman. Oops! She turns and runs and Ahriman, slowed by wading through sand, is unable to catch up. She makes her escape.

Killing directly, with a witness present, has Ahriman in a most vulnerable position, the more so because he does not have mind control over the Keanuphobe and therefore cannot erase her memory. She is also rich enough to afford security and prominent enough that killing her would attract a great deal of attention. But Ahriman has one advantage -- she is a paranoid, and he has a psychological training to manipulate her. Although he has not used his psychological training much, preferring to use mind control, it is real, and he knows what to do with it. The patient has watched every Keanu Reeves movie many times over. So Ahriman calls her and convinces her that The Matrix is real. (The Matrix had just come out when the book was written). Really we are all living in pods in a false reality controlled by an evil computer. Needless to say, this would have been totally ineffective against any normal person, but dealing with a paranoid, it is perfect.

The sinister plot to take over the world does have one advantage, though. It means that Ahriman is no longer the puppet master in control of everything, in fact, he is no longer any more than a bit player. And with Ahriman no longer in control, he can be used for comic relief. There is always an obvious risk in the comic villain, of course. Laughter is generally incompatible with either hate or fear, so a comic villain tends not to be so menacing or so truly evil as a serious one. But then again, Ahriman has already established his evil to everyone's satisfaction, and seeing the puppet master lose control can be the best revenge. This is the first time reading about Ahriman has actually been fun, so let us savor it for a change.

Ahriman has a new patient with a most creative and original phobia that Ahriman had no role in creating. She is the wife of one of those entrepreneurs who were rampant in the 1990's who made a half billion dollar fortune selling

Interestingly to note, her name is never given. She is simply referred to as the Keanuphobe or, later, when our heroes see her in a pink suit, as the pink lady. Her lack of a name is striking. Normally, Koontz gives even very minor characters names. For instance, all personnel at the New Life Clinic have names. The nurses who attend Skeet, the doctor on call, the security guard who makes a total of two short appearances, and even the head nurse, whose single appearance takes a single page, has a name. The lab tech who draws Martie's blood for testing has a name. The police who respond to Susan's suicide have names. A few waiters, sales people, and the security guard in the gated community where Skeet attempts suicide do not have names, and that makes sense. They are seen only from the perspective of Dusty (or Ahriman). Since the person seeing them does not know their name, it is not given. Thus far the only other character whose name is known to a POV (point of view) character whose name is not given is the unnamed Famous Actor who Ahriman programs to bite the President's nose off. Koontz unwillingness to name the Famous Actor (other than to say he is not Keanu Reeve) is understandable. It he actually identified a real famous actor, calling him a drug addict and as stupid as the character is portrayed, he might get in trouble with the actor's lawyers. And if he made up a name, people would complain that for such a famous actor, they have never heard of him. But in any case, Famous Actor is a minor character. We lose very little by not knowing his name. The Keanuphobe (as we shall see) plays a major, indeed, critical, role in the story. Are Internet con men so famous that Koontz couldn't make up a name for one and his wife?

In any event, while shopping and eating lunch, Ahriman notices a red-faced man driving a beat-up old camper truck seems to be watching him. Furthermore, wherever he drives, the beat-up truck follows. The man's name is not given because Ahriman does not know it. But we do. The truck has two very strange antennae on it, and the red-faced man has a passenger -- Skeet. Ahriman has his manservant take his other car to the parking lot next door. He then has his secretary, Jennifer, drive his car to the dealership for maintenance and trails the two men trailing him. Once Jennifer drops off the car, she takes off walking because she is a health and fitness nut. Skeet and Fig follow her. Comic scenes ensue. Ahriman knows that, as a health and fitness nut, Jennifer will eat at Green Acres, a health food restaurant. His own tastes run more to sweets, as unhealthy as possible, so we get an entertaining scene of him looking around the counter for something he would be willing to eat. There are actually some chocolate coconut bars "no butter, margarine, or hydrogenated vegetable shortening," but he takes them anyhow, at a discount because the hostess is so relieved to be rid of them. He also makes comical observations about Skeet and Fig's poor surveillance technique and increasingly starts thinking of Jennifer as a horse, given her taste in food. He wonders if Skeet and Fig are gay lovers, and if he could endure the sight of them in action while shooting them. And he notices a white Rolls Royce at Green Acres and wonders how anyone with the wealth and taste to drive such a car could eat at such a place. (Any guesses what unnamed character that is?).

Fig and Skeet follow Jennifer home and are followed by Ahriman. When she goes in and nothing further happens, they take the dog out, let him poop, and then collect it in a blue bag and throw it in the trash. Ahriman retrieves it, not knowing yet what he intends to do with it. (This, too, will be significant and comical). He trails Fig and Skeet to the beach. They wade out into the ocean with their electronic gear, trying to contact UFO's. Ahriman is baffled, but doesn't have time to figure it out. Instead, he shoots them in the chest. "Your mother's a whore, your father's a fraud, and your stepfather's got pig shit for brains," says Ahriman to Skeet. And this, on page 527, is our first hint that this particular family may be more than random victims to Ahriman. Just as he is about to shoot the dog, he notices that it is barking at someone behind him. He turns around and sees the unnamed Keanuphobe. Yes, the white Rolls Royce was hers, and while Fig and Skeet were following Jennifer and Ahriman was following Fig and Skeet, the Keanuphobe was following Ahriman. Oops! She turns and runs and Ahriman, slowed by wading through sand, is unable to catch up. She makes her escape.

Killing directly, with a witness present, has Ahriman in a most vulnerable position, the more so because he does not have mind control over the Keanuphobe and therefore cannot erase her memory. She is also rich enough to afford security and prominent enough that killing her would attract a great deal of attention. But Ahriman has one advantage -- she is a paranoid, and he has a psychological training to manipulate her. Although he has not used his psychological training much, preferring to use mind control, it is real, and he knows what to do with it. The patient has watched every Keanu Reeves movie many times over. So Ahriman calls her and convinces her that The Matrix is real. (The Matrix had just come out when the book was written). Really we are all living in pods in a false reality controlled by an evil computer. Needless to say, this would have been totally ineffective against any normal person, but dealing with a paranoid, it is perfect.

Previously she had sensed enemies on all side,s with numerous, often inexplicable, and frequently conflicting motives, whereas now she had one enemy to focus upon: the giant, evil world-dominating computer and its drone machines. . . . As a paranoid, she was convinced that reality as the mass of humanity accepted it was a sham, that the truth was stranger and more fearsome than the false reality that most people accepted, and now the doctor was confirming her suspicions. He was offering paranoia with a logical format and a comforting sense of order, which ought to be irresistible.At the same time, Ahriman has to be aware that he is losing control of the situation. He is talking the most outrageous nonsense to a crazy person and becoming aware that he is starting to sound (and feel) crazy himself. His goal is to get the Keanuphobe to come to his office so that he can program her and make the problem go away. He is hopeful.

Saturday, November 17, 2012

One Reality Republicans May Take Away from This Election

I would also like to add one little second thought on whether this election will force Republicans to face unpleasant facts. Last time I was skeptical, believing that while reality is extremely difficult to deny when it comes to election outcomes, more complex and remote realities will remain deniable. But I am beginning to think that was too glib. I personally would not put too much stock in people who direly warn that Republicans have lost the popular vote in five of the last six elections. Quite simply, the popular vote from 1992 onward has been fairly close. But I think Republicans are finally beginning to face facts and realize that their glory days of 1980 to 1988 are not coming back.

It was never any mystery to me why Republicans hated Bill Clinton so much. He was a Democrat and he was President. Nothing more was needed.

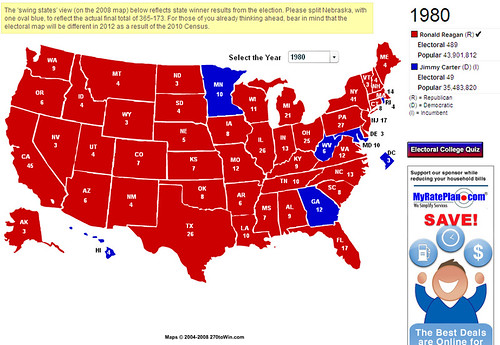

In 1980, Ronald Reagan won an electoral college landslide over Jimmy Carter of 489 to 49.

In 1984, Reagan won an even greater landslide against Walter Mondale, 525 electoral votes to 13.

1988 was less overwhelming, but the senior Bush nonetheless won over Michael Dukakis by the the comfortable margin of 426 electoral votes to 112. Democrats were developing the reputation (in the words of David Barry) of not being qualified to plug in an electric blanket, let alone win the Presidency. And Republicans developed what every conservative professes to hate the most -- a sense of entitlement. In particular, they developed a sense of entitlement to the Presidency and to assume that the sorts of electoral landslides that had gotten as a matter of routine in the 1980's would be theirs forever. This sense was strengthened when the senior Bush fought the Gulf War, 1990-1991 against the advice of many Democrats, made a quick and easy victory, and seemed invulnerable going into the 1992. Then a recession hit and the Democrats won.

It should be noted, by the way, that what brought Ronald Reagan to power was the stagflation of the 1970's -- a combination of a weak economy and double digit inflation. Reagan agreed to back Paul Volcker of the Federal Reserve in the painful but necessary measure necessary to break the inflationary spiral -- tightening the money supply, no matter how painful, until inflation cried uncle. With Reagan's backing, Volcker put the squeeze on the economy, raising interest rates as high as 20%, and throwing the economy into a severe recession. But the inflationary spiral was broken. As soon as Volcker was satisfied that inflation was under control, he let up on the brakes, and the economy quickly rebounded. It was at the very peak of growth (returning to capacity) at the time of the 1984 election. I recall well at the time that George Will mocked overly enthusiastic Republicans who thought that Reagan has repealed the laws of business cycles and that we would have prosperity forever. And, indeed, no one came right out and said so, but certainly the implied promise was that, after suffering so severe a recession in 1981-1982, we would be rewarded by never experiencing one again. As long as this appeared to be the case, Republicans continued to win the Presidency by landslides. But inevitably, recession reared its ugly head again, people were shocked to realize that the business cycle was still with us, and Clinton won. Republicans dismissed his victory as an anomaly because Ross Perot was running a third party candidacy. Republicans presumed that every vote for Perot would otherwise have gone to a Republican and were therefore able to dismiss Clinton's victories in 1992 and 1996 as illegitimate, because he never won a popular majority.

In 2000, the junior Bush won a razor-thin electoral majority of 271-267 and actually narrowly lost the popular vote. But because the states that went for Bush were less densely populated than the ones that voted for Gore, they were geographically larger, and electoral maps created a misleading impression of a strong Bush majority.

In 2004, Bush did win the popular vote and had a more comfortable electoral margin of 301-237. But, once again, geography was misleading, and his advantage in rural areas made his margin of victory look much wider than it really was. Thus, although Republicans should have recognized that their glory days of the 1980's were long gone, they looked at the electoral map and saw a landslide.

In 2008, the country suffered its worst financial crisis since the Great Depression, and, unsurprisingly, the incumbent party lost. Obama got an absolute popular majority a strong electoral college victory of 375-163. The peculiarities of geography made this victory appear less than it was, but the impression of an overwhelming red state majority was no longer possible to maintain. Republicans still refused to accept the results. Just as the 1990's wins of Bill Clinton could be dismissed as anomalies because Ross Perot's third party candidacy skewed the results, Obama's 2008 victory could be dismissed as an anomaly because of an economic crisis and unrealistic expectations as to what he could do about it. Republicans assumed that if they only held the line for four years, the natural order would reassert itself, and the would once again hold the White House, as was their right. They could still dismiss three of the last five Presidential elections a anomalies that would not be repeated.

Then 2012 struck. This election was not so easy to dismiss as an anomaly. This time there was no third party candidate to skew the results. The economy was lackluster. And yet, the Democrat won once again. Furthermore, the electoral map was vary similar to the last one, suggesting that a stable coalition was in place. The contrast to what certain Republican pollsters had been predicting was stunning.

What happened, so far as I can tell, was that the Democrats won an election under unfavorable circumstances, one that cannot be explained away by a third party candidate or an economic crisis. And suddenly Republicans are beginning to recognized that their landslides of the 1980's are over for the foreseeable future. Worse yet, they are beginning to come to grips with the fact that the presence of a Democrat in the White House is not some sort of bizarre anomaly, or an outrage against the natural order, but a normal occurrence.

If they are able to assimilate that into the world view, then we may, indeed, begin to see the beginning of the decline of the madness. At least I can hope.

It was never any mystery to me why Republicans hated Bill Clinton so much. He was a Democrat and he was President. Nothing more was needed.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan won an electoral college landslide over Jimmy Carter of 489 to 49.

In 1984, Reagan won an even greater landslide against Walter Mondale, 525 electoral votes to 13.

1988 was less overwhelming, but the senior Bush nonetheless won over Michael Dukakis by the the comfortable margin of 426 electoral votes to 112. Democrats were developing the reputation (in the words of David Barry) of not being qualified to plug in an electric blanket, let alone win the Presidency. And Republicans developed what every conservative professes to hate the most -- a sense of entitlement. In particular, they developed a sense of entitlement to the Presidency and to assume that the sorts of electoral landslides that had gotten as a matter of routine in the 1980's would be theirs forever. This sense was strengthened when the senior Bush fought the Gulf War, 1990-1991 against the advice of many Democrats, made a quick and easy victory, and seemed invulnerable going into the 1992. Then a recession hit and the Democrats won.

It should be noted, by the way, that what brought Ronald Reagan to power was the stagflation of the 1970's -- a combination of a weak economy and double digit inflation. Reagan agreed to back Paul Volcker of the Federal Reserve in the painful but necessary measure necessary to break the inflationary spiral -- tightening the money supply, no matter how painful, until inflation cried uncle. With Reagan's backing, Volcker put the squeeze on the economy, raising interest rates as high as 20%, and throwing the economy into a severe recession. But the inflationary spiral was broken. As soon as Volcker was satisfied that inflation was under control, he let up on the brakes, and the economy quickly rebounded. It was at the very peak of growth (returning to capacity) at the time of the 1984 election. I recall well at the time that George Will mocked overly enthusiastic Republicans who thought that Reagan has repealed the laws of business cycles and that we would have prosperity forever. And, indeed, no one came right out and said so, but certainly the implied promise was that, after suffering so severe a recession in 1981-1982, we would be rewarded by never experiencing one again. As long as this appeared to be the case, Republicans continued to win the Presidency by landslides. But inevitably, recession reared its ugly head again, people were shocked to realize that the business cycle was still with us, and Clinton won. Republicans dismissed his victory as an anomaly because Ross Perot was running a third party candidacy. Republicans presumed that every vote for Perot would otherwise have gone to a Republican and were therefore able to dismiss Clinton's victories in 1992 and 1996 as illegitimate, because he never won a popular majority.

In 2000, the junior Bush won a razor-thin electoral majority of 271-267 and actually narrowly lost the popular vote. But because the states that went for Bush were less densely populated than the ones that voted for Gore, they were geographically larger, and electoral maps created a misleading impression of a strong Bush majority.

In 2004, Bush did win the popular vote and had a more comfortable electoral margin of 301-237. But, once again, geography was misleading, and his advantage in rural areas made his margin of victory look much wider than it really was. Thus, although Republicans should have recognized that their glory days of the 1980's were long gone, they looked at the electoral map and saw a landslide.