But before I continue with some of the problems that result from guaranteeing everyone the right to form a private army dedicated to the violent overthrow of the US government, I want to move into another topic that has been tantalizing me for some time -- Colleen McCullough's Masters of Rome series. So far, I have read the first book, First Man of Rome, starring Gaius Marius as the title character. Really, I shouldn't be getting to Rome before finishing Greece, and I should start with non-fiction before moving into fiction, but the series has been a temptation to me ever since reading Shakespeare's Julius Caesar for a more favorable look at the man himself. (Although he has just been born at the end of First Man in Rome).

I have now read the first book, and while it would be an exaggeration to say that I couldn't put it down and was walking around reading it and bumping into things, it did absorb my attention to the point of neglecting other things I probably should have been doing (like posting here), and I got through it faster than would ever seem possible for a 781 page novel.

I also read it at several levels. One was purely a literary level, approaching it as a work of literature, albeit one bounded by actual historical events. One was as a historical novel -- how well does it match actual historical events. And one was as a political novel, seen from the perspective of my consuming obsession -- the failure of democratically elective government, in this case, the Roman Republic.

So I intend to discuss it in (a minimum of) three posts -- first as a pure work of literature, second as a political novel, and third, to compare it to historical events and see how accurate it is.

Saturday, June 28, 2014

First Man of Rome: A Short Introduction

Friday, June 27, 2014

Presser v. Illinois

There is at least one Supreme Court case that addresses whether the Second Amendment authorizes private armies -- the case of Presser v. Illinois. This case, like Luther v. Borden, is troubling from today's perspective precisely because it does not allow armed resistance to injustice. Yet, like Luther, it is also useful as a reminder that, even in the case of serious injustice, armed rebellion is a terrible thing and not one to be taken lightly or romanticized.

A little background is in order that the opinion is less than clear about. The case took place in the Gilded Age, when labor violence was at an all-time high in this country. Powerful companies hired the Pinkerton Detectives and other private goons as their de facto private armies. Unions countered them by raising their own armed forces, in this case, with the Socialist Labor Party. For this Presser, the head of the armed company, was charged with violating an Illinois statute forbidding military organizations other than those authorized by the state. As a defense, Presser argued that the statute violated his Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms. (Unsurprisingly, no such charges were brought against armed forces for powerful companies).

The Supreme Court decision is in some ways deeply offensive to our present-day understanding of the Constitution, but in other ways still current. It took the view current at the time distinguishing between the rights of "citizens of the United States," which were protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, and citizens of a state. In particular, most of the Bill of Rights was held to be a restriction only on the Federal Government and not the states:

Presser also avoided addressing the issue of whether the Illinois Military Code was in violation of Article I, Section 10, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, forbidding states from keeping troops other than the militia authorized by Article I, Section 8, Clauses 15 and 16. But it did make clear that states could ban private armies, and its basic reasoning is sound, even if it was unjustly applied in this particular instance:

And the unequal way in which the ban on private armies was enforced raises another question that applies to the Patriot movement to this day, and that I plan to address in the near future -- if the Second Amendment guarantees a right to private armies and armed rebellion, just who is guaranteed that right.

A little background is in order that the opinion is less than clear about. The case took place in the Gilded Age, when labor violence was at an all-time high in this country. Powerful companies hired the Pinkerton Detectives and other private goons as their de facto private armies. Unions countered them by raising their own armed forces, in this case, with the Socialist Labor Party. For this Presser, the head of the armed company, was charged with violating an Illinois statute forbidding military organizations other than those authorized by the state. As a defense, Presser argued that the statute violated his Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms. (Unsurprisingly, no such charges were brought against armed forces for powerful companies).

The Supreme Court decision is in some ways deeply offensive to our present-day understanding of the Constitution, but in other ways still current. It took the view current at the time distinguishing between the rights of "citizens of the United States," which were protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, and citizens of a state. In particular, most of the Bill of Rights was held to be a restriction only on the Federal Government and not the states:

The provision in the Second Amendment to the Constitution, that "The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed" is a limitation only on the power of Congress and the national government, and not of the states. But in view of the fact that all citizens capable of bearing arms constitute the reserved military force of the national government as well as in view of its general powers, the states cannot prohibit the people from keeping and bearing arms so as to deprive the United States of their rightful resource for maintaining the public security.

The provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution that "No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States" does not prevent a state from passing such laws to regulate the privileges and immunities of its own citizens as do not abridge their privileges and immunities as citizens of the United States.In this it cited the odious case of US v. Cruikshank, a case that deserves to live in the same infamy as Dred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson, holding, in effect, that armed vigilantes in the South could deprive black people of their rights to their hearts' content, and the Federal Government could not intervene. But one can condemn Presser for citing Cruikshank and still regard it as sound in other ways.

Presser also avoided addressing the issue of whether the Illinois Military Code was in violation of Article I, Section 10, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, forbidding states from keeping troops other than the militia authorized by Article I, Section 8, Clauses 15 and 16. But it did make clear that states could ban private armies, and its basic reasoning is sound, even if it was unjustly applied in this particular instance:

Military organization and military drill and parade under arms are subjects especially under the control of the government of every country. They cannot be claimed as a right independent of law. Under our political system, they are subject to the regulation and control of the state and federal governments, acting in due regard to their respective prerogatives and powers. . . . The exercise of this power by the states is necessary to the public peace, safety, and good order. To deny the power would be to deny the right of the state to disperse assemblages organized for sedition and treason, and the right to suppress armed mobs bent on riot and rapine.And though we may be appalled at the narrow reading of the Bill of Rights at the time, that applied it only to the Federal Government and not the states, and although we may be offended that the double standard here, enforcing the ban on private armies only against labor and not against management, let us concede the opinion a point here that remains just as valid to this day. Military organization and drill and parade under arms are, or at least should be, subjects especially under the control of the government in every country. To allow unchecked proliferation of private armies is, indeed, an invitation to anarchy.

And the unequal way in which the ban on private armies was enforced raises another question that applies to the Patriot movement to this day, and that I plan to address in the near future -- if the Second Amendment guarantees a right to private armies and armed rebellion, just who is guaranteed that right.

Wednesday, June 25, 2014

Regulatory Capture: It's Not Just About Regulatory Agencies

And on the phenomenon of regulatory capture, the term should be applied in a broader context than just regulatory agencies being captured by the industries they regulate. Any time the Watchers go from outsider to insider, regulatory capture becomes an issue. Consider:

Surveillance. Attempts to regulate government surveillance and intelligence were made in the 1970's following the Church Hearings. The Senate and House Intelligence Committees were given greater oversight over executive intelligence agencies. The FISA court was created to decide whether foreign intelligence surveillance was warranted. Both attempts have proven toothless. Congressional intelligence committees have simply been coopted into the intelligence system and provide no meaningful oversight. The FISA court has been reduced to a rubber stamp, routinely approving requests like a warrant to gather meta-data on all telephone calls in the country. So far as I can tell, what happened in both cases was that outsiders who originally came in wanting to exercise meaningful oversight became insiders and part of the system.

The press corps. These are supposed to be the watchdogs who keep government honest. Instead, they have become increasingly deferential to the powerful for fear of losing access if they publish anything critical. The press has gone from outsider to insider and been captured by -- government.

Doubtless there are many other examples that can be found. The point here, I think, is that regulatory capture is not evidence of something especially noxious about government regulation, but part of the general tendency of outsiders to become insiders and insiders to protect their own. The question is what to do about it.

Surveillance. Attempts to regulate government surveillance and intelligence were made in the 1970's following the Church Hearings. The Senate and House Intelligence Committees were given greater oversight over executive intelligence agencies. The FISA court was created to decide whether foreign intelligence surveillance was warranted. Both attempts have proven toothless. Congressional intelligence committees have simply been coopted into the intelligence system and provide no meaningful oversight. The FISA court has been reduced to a rubber stamp, routinely approving requests like a warrant to gather meta-data on all telephone calls in the country. So far as I can tell, what happened in both cases was that outsiders who originally came in wanting to exercise meaningful oversight became insiders and part of the system.

The press corps. These are supposed to be the watchdogs who keep government honest. Instead, they have become increasingly deferential to the powerful for fear of losing access if they publish anything critical. The press has gone from outsider to insider and been captured by -- government.

Doubtless there are many other examples that can be found. The point here, I think, is that regulatory capture is not evidence of something especially noxious about government regulation, but part of the general tendency of outsiders to become insiders and insiders to protect their own. The question is what to do about it.

Libertarians and "Plutocratic Capture"

Paul Krugman has written another column that expresses my basic concerns for our future. He comments that conservative economists (i.e., libertarians) worry about regulatory capture, i.e., that regulatory agencies will end up being captured by the industries they are supposed to regulate, but not about "plutocratic capture," i.e., that extreme concentration of wealth will lead to the one percent hijacking democratic institutions.

I don't think that is quite right. In my experience, libertarians are well aware of the dangers of plutocratic capture; they just differ from liberals on what to do about it. I confess I am not clear as to what liberals propose to do about regulatory capture. To libertarians the answer is easy -- no regulations, no regulatory capture. Just don't regulate and regulatory capture will be a non-issue.

I have a better sense of the liberal answer to plutocratic capture. It comes in two basic parts. One is to avoid extreme concentration of wealth, whether by redistributive taxation or otherwise. The other is to have other strong power centers in society to counter the strength of the plutocracy -- such as unions, consumer organization, home owner associates, or government. It is a bit glib to say that libertarians' approach to plutocratic capture is the same -- no government, no plutocratic capture. But that is more caricature than total misrepresentation. Libertarians tend to assume that the way to avoid plutocratic capture is to keep government as small and as weak as possible so that it won't be worth capturing. The unstated assumption here is that if plutocrats are not able to exercise power by capturing a strong government, then they will have no power and the rest of us will not have to fear its abuse.

I consider the libertarian viewpoint to be hopelessly naive. It is true, I agree, that the combination of a strong, active state and extreme concentration of wealth creates the danger of plutocratic capture -- of the rich treating the state as their private instrument. But there are two problems with the assumption that keeping the state small and weak will avoid these dangers.

First of all, just how small and weak does the state have to be? After all, the state was much smaller and weaker in the Gilded Age than it is today, yet powerful concentrations of wealth nonetheless thought it worth capturing. Some libertarians describe the state as a monopoly on violence and conclude that it exceeds its proper limits whenever it does anything other than violence. Well, powerful interests of the Gilded Age were entirely happy to use the state's monopoly on violence as an instrument on their behalf to crush unions. But I suppose a libertarian might argue that with today's increased mobility of capital, in the absence of artificial limitations, a company might simply fire any troublesome union organizers and, if this failed to work, relocate to somewhere without unions, so there would be no need to resort to brute force. Other libertarians want to limit the state to the criminal justice system and a civil court system. But the effect of this would simply be to shift the arena for contesting concentrations of economic power to the courts. For instance, if we end all environmental regulation, the best recourse for a victim of a polluting company would be a common law action enjoin a nuisance. But that would not so much shrink the power of the state as shift it to the courts, and thereby give the rich and powerful a strong interest in wanting to capture the process for choosing judges. Other libertarians allow a greater scope for the state, but in that case the state would clearly be worth capturing. In short, I do not think it possible to make the state too small and weak to be worth capturing.

But even assuming we can shrink the state to the point that it is not worth capturing, libertarians are quite wrong in assuming that this will prevent abuses of power by great concentrations of wealth. What actually happens when a society combines great inequality of wealth with a small and weak state is that the rich use their power to form their own state-within-a-state, which they use entirely for their private interests because there is no pretense of public accountability.

We are already seeing an early and relatively benign form of this in the form of gated communities. Gate communities hire their own private security guards -- and resist paying taxes for community police forces. Likewise, people who can afford to may send their children to private schools. They may resist paying taxes for public schools, but even if they do not, public schools lose important advocates and participants. Powerful companies are bypassing the courts by putting arbitration clauses into their contracts and assuring that any dispute under the contract will be arbitrated in a forum favorable to the company. Libertarians will probably defend all these things as appropriate exercises in self-interest, and as proof that the private sector does these things better than government. But to individuals who cannot afford their own private security guards, or private schools, or arbitration forums, the result is an undercutting of public services and access to the courts.

Nor does the state-within-a-state necessarily stop there. In many countries with strong concentration of wealth and a weak state, the rich invade the state's monopoly on violence to form their own private forces, like the Pinkerton Detectives or Latin American death squads. In its most extreme forms, the state can break down altogether and the rich and powerful become warlords.

All of which points up to the central error of libertarianism -- its assumption that the state has a monopoly on power and oppression, that if one eliminates the state, on eliminates power and its potential for abuse.

I don't think that is quite right. In my experience, libertarians are well aware of the dangers of plutocratic capture; they just differ from liberals on what to do about it. I confess I am not clear as to what liberals propose to do about regulatory capture. To libertarians the answer is easy -- no regulations, no regulatory capture. Just don't regulate and regulatory capture will be a non-issue.

I have a better sense of the liberal answer to plutocratic capture. It comes in two basic parts. One is to avoid extreme concentration of wealth, whether by redistributive taxation or otherwise. The other is to have other strong power centers in society to counter the strength of the plutocracy -- such as unions, consumer organization, home owner associates, or government. It is a bit glib to say that libertarians' approach to plutocratic capture is the same -- no government, no plutocratic capture. But that is more caricature than total misrepresentation. Libertarians tend to assume that the way to avoid plutocratic capture is to keep government as small and as weak as possible so that it won't be worth capturing. The unstated assumption here is that if plutocrats are not able to exercise power by capturing a strong government, then they will have no power and the rest of us will not have to fear its abuse.

I consider the libertarian viewpoint to be hopelessly naive. It is true, I agree, that the combination of a strong, active state and extreme concentration of wealth creates the danger of plutocratic capture -- of the rich treating the state as their private instrument. But there are two problems with the assumption that keeping the state small and weak will avoid these dangers.

First of all, just how small and weak does the state have to be? After all, the state was much smaller and weaker in the Gilded Age than it is today, yet powerful concentrations of wealth nonetheless thought it worth capturing. Some libertarians describe the state as a monopoly on violence and conclude that it exceeds its proper limits whenever it does anything other than violence. Well, powerful interests of the Gilded Age were entirely happy to use the state's monopoly on violence as an instrument on their behalf to crush unions. But I suppose a libertarian might argue that with today's increased mobility of capital, in the absence of artificial limitations, a company might simply fire any troublesome union organizers and, if this failed to work, relocate to somewhere without unions, so there would be no need to resort to brute force. Other libertarians want to limit the state to the criminal justice system and a civil court system. But the effect of this would simply be to shift the arena for contesting concentrations of economic power to the courts. For instance, if we end all environmental regulation, the best recourse for a victim of a polluting company would be a common law action enjoin a nuisance. But that would not so much shrink the power of the state as shift it to the courts, and thereby give the rich and powerful a strong interest in wanting to capture the process for choosing judges. Other libertarians allow a greater scope for the state, but in that case the state would clearly be worth capturing. In short, I do not think it possible to make the state too small and weak to be worth capturing.

But even assuming we can shrink the state to the point that it is not worth capturing, libertarians are quite wrong in assuming that this will prevent abuses of power by great concentrations of wealth. What actually happens when a society combines great inequality of wealth with a small and weak state is that the rich use their power to form their own state-within-a-state, which they use entirely for their private interests because there is no pretense of public accountability.

We are already seeing an early and relatively benign form of this in the form of gated communities. Gate communities hire their own private security guards -- and resist paying taxes for community police forces. Likewise, people who can afford to may send their children to private schools. They may resist paying taxes for public schools, but even if they do not, public schools lose important advocates and participants. Powerful companies are bypassing the courts by putting arbitration clauses into their contracts and assuring that any dispute under the contract will be arbitrated in a forum favorable to the company. Libertarians will probably defend all these things as appropriate exercises in self-interest, and as proof that the private sector does these things better than government. But to individuals who cannot afford their own private security guards, or private schools, or arbitration forums, the result is an undercutting of public services and access to the courts.

Nor does the state-within-a-state necessarily stop there. In many countries with strong concentration of wealth and a weak state, the rich invade the state's monopoly on violence to form their own private forces, like the Pinkerton Detectives or Latin American death squads. In its most extreme forms, the state can break down altogether and the rich and powerful become warlords.

All of which points up to the central error of libertarianism -- its assumption that the state has a monopoly on power and oppression, that if one eliminates the state, on eliminates power and its potential for abuse.

Tuesday, June 24, 2014

Beware R > G

I have not read Thomas Picketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century, but really I probably should. Its basic hypothesis is simple:: Historic trend is for return on assets to grow faster than the overall economy, leading to ever increased concentration of wealth. We broke from trend for a while, but are returning to it. Or, to put it more simply, the rate of return on assets is greater than overall economic growth. R > G, in economic speak. That could explain a lot.

As I understand it, Picketty focuses mostly on modern times, but modern times have been unusual. His data apparently goes all the way back to 0 A.D. and shows that historically, the return on assets has generally been around 4.5%, going up slightly to about 5% around the time of the Industrial Revolution. World economic growth has never been this high.* Indeed, world economic growth was minimal from 0 to 1000 and under 1% until the Industrial Revolution got going. R abnormally dropped to around 1% around 1913-1950; G reached the extraordinary height approaching 4% (still below the historical return on assets, bear in mind) between 1950 and the present, while R has been moving toward its historical level, but remains (narrowly) below G. Picketty presupposes that R will return to its historic level, while G falls, though not all the way to its historic level.

This graph (and, presumably, Picketty's book) does not go back to pre-0 A.D., but his hypothesis could explain a lot. Because so far as I can tell, the failure of democratically elective government in Classical Antiquity can roughly be summed up as R > G. There was (I assume) real economic growth in classical Greece and Rome (remember, the G in the graph is world economic growth). The wealth became increasingly concentrated, while growing portions of the population became impoverished. In Rome, at least, a lot of what was happening was the growth of vast slave plantations that really could grow more food with less labor -- but the result of supporting a larger population with less work was massive unemployment. England suffered the same problem pre-Industrial Revolution and ultimately solved it with industrialization. In Classical times, no such resolution was found. Wealth simply accumulated in fewer and fewer hands and more and more people were poor and unemployed, with no relief in sight. The details, of course, differed from time to time and place to place, and I look forward to learning about them. But underlying it all was the iron law of R > G.

And Picketty's hypothesis, if true, has scary implications for the future. I do not expect R > G to be as much of an issue in the modern failure of democracy as in Classical times (although do not forget that democracy is most likely to fail when a country's G falls) because the massive increase in G from industrial development came to the rescue. But if Picketty is right, and if others are right in their fears that automation will make people obsolete, we could end up right back where so many other societies -- from Classical Greece and Rome to England before the Industrial Revolution -- great at producing stuff, but unable to make room for large portions of the population.

R > G may prove to be a major difference in failing democracy in Classical versus modern times.

_____________________________________________

*Economic growth has reached and exceeded this level in individual countries, but only up to a point, and never world-wide.

As I understand it, Picketty focuses mostly on modern times, but modern times have been unusual. His data apparently goes all the way back to 0 A.D. and shows that historically, the return on assets has generally been around 4.5%, going up slightly to about 5% around the time of the Industrial Revolution. World economic growth has never been this high.* Indeed, world economic growth was minimal from 0 to 1000 and under 1% until the Industrial Revolution got going. R abnormally dropped to around 1% around 1913-1950; G reached the extraordinary height approaching 4% (still below the historical return on assets, bear in mind) between 1950 and the present, while R has been moving toward its historical level, but remains (narrowly) below G. Picketty presupposes that R will return to its historic level, while G falls, though not all the way to its historic level.

This graph (and, presumably, Picketty's book) does not go back to pre-0 A.D., but his hypothesis could explain a lot. Because so far as I can tell, the failure of democratically elective government in Classical Antiquity can roughly be summed up as R > G. There was (I assume) real economic growth in classical Greece and Rome (remember, the G in the graph is world economic growth). The wealth became increasingly concentrated, while growing portions of the population became impoverished. In Rome, at least, a lot of what was happening was the growth of vast slave plantations that really could grow more food with less labor -- but the result of supporting a larger population with less work was massive unemployment. England suffered the same problem pre-Industrial Revolution and ultimately solved it with industrialization. In Classical times, no such resolution was found. Wealth simply accumulated in fewer and fewer hands and more and more people were poor and unemployed, with no relief in sight. The details, of course, differed from time to time and place to place, and I look forward to learning about them. But underlying it all was the iron law of R > G.

And Picketty's hypothesis, if true, has scary implications for the future. I do not expect R > G to be as much of an issue in the modern failure of democracy as in Classical times (although do not forget that democracy is most likely to fail when a country's G falls) because the massive increase in G from industrial development came to the rescue. But if Picketty is right, and if others are right in their fears that automation will make people obsolete, we could end up right back where so many other societies -- from Classical Greece and Rome to England before the Industrial Revolution -- great at producing stuff, but unable to make room for large portions of the population.

R > G may prove to be a major difference in failing democracy in Classical versus modern times.

_____________________________________________

*Economic growth has reached and exceeded this level in individual countries, but only up to a point, and never world-wide.

Labels:

Failures of Democracy,

General macro,

History

Monday, June 23, 2014

Memo to Google

To: Google

From: Your readers

Re: World Cup Soccer

Message: We have noticed a lot of World Cup related themes up there when we do Google searches lately. We get that you are big soccer fans and all excited about the World Cup. And it is cute. But really, enough is enough after a while. Can't you come up with something else just as cute?

From: Your readers

Re: World Cup Soccer

Message: We have noticed a lot of World Cup related themes up there when we do Google searches lately. We get that you are big soccer fans and all excited about the World Cup. And it is cute. But really, enough is enough after a while. Can't you come up with something else just as cute?

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

Dear President Obama: Talk to Congress Before Starting Any Wars

Dear President Obama:

Apparently you believe that you have authority to intervene in Iraq without consulting Congress. So let me make this heartfelt appeal to you. Talk to Congress before you do anything rash.

There are two reasons you should do this, one a matter of policy and one of politics.

As a matter of policy, we have had more than too many Presidents fighting unilateral, unauthorized wars. Granted, this is not new. As a matter of fact, it has been happening since Thomas Jefferson sent the Marines to the shores of Tripoli. But enough is enough. The decision to go to war (even a small war) is to large a decision to be made by one man. It is a decision for the nation, to be made through its representatives in Congress. Granted, in times past and no doubt times future Congress has not served as much of a brake on out-of-control Presidents. But the nation is war weary and war wary. If we are going to have a war, even on a small scale, it needs talking over before you do something stupid.

As for the matter of politics, in acting unilaterally, you leave yourself vulnerable. Make no mistake, regardless of what you do, the Republicans will condemn you for it and say you should have done the opposite. So instead of giving them the opening, force them to commit. Granted, they will still blame you for withdrawing and insist that if you had just lest a small residual force, all would be well today. Well, don't worry. No one believes them. Not even Glen Beck, for God's sake! So go ahead. Before you act, make them stand up and commit.

With any luck, they will block you.

Apparently you believe that you have authority to intervene in Iraq without consulting Congress. So let me make this heartfelt appeal to you. Talk to Congress before you do anything rash.

There are two reasons you should do this, one a matter of policy and one of politics.

As a matter of policy, we have had more than too many Presidents fighting unilateral, unauthorized wars. Granted, this is not new. As a matter of fact, it has been happening since Thomas Jefferson sent the Marines to the shores of Tripoli. But enough is enough. The decision to go to war (even a small war) is to large a decision to be made by one man. It is a decision for the nation, to be made through its representatives in Congress. Granted, in times past and no doubt times future Congress has not served as much of a brake on out-of-control Presidents. But the nation is war weary and war wary. If we are going to have a war, even on a small scale, it needs talking over before you do something stupid.

As for the matter of politics, in acting unilaterally, you leave yourself vulnerable. Make no mistake, regardless of what you do, the Republicans will condemn you for it and say you should have done the opposite. So instead of giving them the opening, force them to commit. Granted, they will still blame you for withdrawing and insist that if you had just lest a small residual force, all would be well today. Well, don't worry. No one believes them. Not even Glen Beck, for God's sake! So go ahead. Before you act, make them stand up and commit.

With any luck, they will block you.

Monday, June 16, 2014

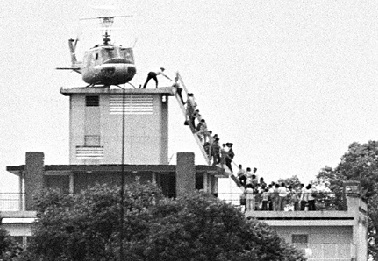

The Fall of Saigon

I am not old enough to remember the Vietnam War, including its conclusion, the fall of Saigon. But from what I have heard about it, events in Iraq are following a familiar pattern. When we withdrew from Vietnam, the Viet Cong were largely eliminated as a force. We were able to cobble together something that could loosely be called victory. We claimed to have achieved peace with honor. And a war-weary public didn't want to hear any more about it.

But the government of South Vietnam we left in power was a frail, artificial construct, too weak to stand on its own. Once we left, it soon collapsed. The North Vietnamese blitzkrieg came charging across the border, and the government we had been propping up fell with little resistance. All pretenses of victory were at an end. We had lost.

Of course, there were hawkish hard liners who considered the situation salvageable to the very end. If only we had gone in and propped up the South Vietnamese government again, we would have been able to turn back the North Vietnamese invasion and all would have been well, or, if not well, back to the status quo ante. The hardliners were mostly Republicans. A Republican President (Nixon) had negotiated the fragile peace that we could pretend was a victory. A Republican President (Ford) was in the White House when Saigon fell. But the Democrats controlled Congress and cut off any funds for continuing the war. So certain unrepentant hard liners always insisted that we could have won if those treacherous Democrats hadn't stabbed a Republican President in the back.

Oh, yes, and once South Vietnam fell, it soon became apparent that, although the government we had been backing were bad guys, the enemy we were fighting were worse. A lot of Americans whose opposition to the war spilled all the way over into support for the enemy had a hard time admitting it.

Fast forward another 40 years, and it looks very similar (though not the same). We managed to cobble together what could roughly be called a victory in Iraq. The Sunnis turned against Al-Qaeda in Iraq and took sides with us in defeating them. The Iraqi government requested -- nay, demanded -- our withdrawal and was in charge when we left. We claimed that the surge worked. And a war-weary public didn't want to hear any more about it.

But the government of Iraq we left behind was a frail, artificial construct, too weak to stand on its own. Once we left, it soon enraged the Sunnis, and they once again started working with AQI and others like it. ISIS is launching its blitzkrieg across the Syrian border, and towns have been falling with little resistance. All pretenses of victory are at an end, or nearly so. If ISIS wins, we have lost.

Of course, there are hawkish hard liners who still consider the situation salvageable. They are convinced that if only we had left a small residual force in Iraq (against the express wishes of the Iraqi government) we could have stopped this from happening, or that a few troops even now will work wonders. But all that either action would achieve would be to continue the situation that most Americans (and Iraqis) found so intolerable and were unwilling to continue. Deep sigh of frustration.

Of course, there are differences between then and now. This time, a Republican negotiated our exit, including the possibility of a small residual force, while a Democrat actually made the exit, without such a force. And the fall of Mosul has taken place with a Democrat in the White House and a Republican Congress. Which means, based on its past record, that Congressional Republicans will scream bloody murder, demanding that Obama intervene until he actually makes some move to do so, whereupon they will scream bloody murder denouncing his actions. Partisanship is a lot sharper now than it was then.

Oh, yes, and this time no one had any illusions about the nature of the people we are fighting. The government we propped up may be bad guys, but no one doubts that ISIS is even worse.

But the government of South Vietnam we left in power was a frail, artificial construct, too weak to stand on its own. Once we left, it soon collapsed. The North Vietnamese blitzkrieg came charging across the border, and the government we had been propping up fell with little resistance. All pretenses of victory were at an end. We had lost.

Of course, there were hawkish hard liners who considered the situation salvageable to the very end. If only we had gone in and propped up the South Vietnamese government again, we would have been able to turn back the North Vietnamese invasion and all would have been well, or, if not well, back to the status quo ante. The hardliners were mostly Republicans. A Republican President (Nixon) had negotiated the fragile peace that we could pretend was a victory. A Republican President (Ford) was in the White House when Saigon fell. But the Democrats controlled Congress and cut off any funds for continuing the war. So certain unrepentant hard liners always insisted that we could have won if those treacherous Democrats hadn't stabbed a Republican President in the back.

Oh, yes, and once South Vietnam fell, it soon became apparent that, although the government we had been backing were bad guys, the enemy we were fighting were worse. A lot of Americans whose opposition to the war spilled all the way over into support for the enemy had a hard time admitting it.

Fast forward another 40 years, and it looks very similar (though not the same). We managed to cobble together what could roughly be called a victory in Iraq. The Sunnis turned against Al-Qaeda in Iraq and took sides with us in defeating them. The Iraqi government requested -- nay, demanded -- our withdrawal and was in charge when we left. We claimed that the surge worked. And a war-weary public didn't want to hear any more about it.

But the government of Iraq we left behind was a frail, artificial construct, too weak to stand on its own. Once we left, it soon enraged the Sunnis, and they once again started working with AQI and others like it. ISIS is launching its blitzkrieg across the Syrian border, and towns have been falling with little resistance. All pretenses of victory are at an end, or nearly so. If ISIS wins, we have lost.

Of course, there are hawkish hard liners who still consider the situation salvageable. They are convinced that if only we had left a small residual force in Iraq (against the express wishes of the Iraqi government) we could have stopped this from happening, or that a few troops even now will work wonders. But all that either action would achieve would be to continue the situation that most Americans (and Iraqis) found so intolerable and were unwilling to continue. Deep sigh of frustration.

Of course, there are differences between then and now. This time, a Republican negotiated our exit, including the possibility of a small residual force, while a Democrat actually made the exit, without such a force. And the fall of Mosul has taken place with a Democrat in the White House and a Republican Congress. Which means, based on its past record, that Congressional Republicans will scream bloody murder, demanding that Obama intervene until he actually makes some move to do so, whereupon they will scream bloody murder denouncing his actions. Partisanship is a lot sharper now than it was then.

Oh, yes, and this time no one had any illusions about the nature of the people we are fighting. The government we propped up may be bad guys, but no one doubts that ISIS is even worse.

Sunday, June 15, 2014

Just want to give a quick hat tip to the linked column by Jonathan Chait to the effect that what really drove opposition to Eric Cantor what not so much the substance of any particular proposal he made, but to the fact that he made any sort of deal with the Democrats at all. He shows how even the most conservative voters are actually split on the issue of immigration and then adds:

Conservative Republicans may not hate immigration reform, but they hate compromise in general. By an 82-14 margin, liberals want their elected officials to make compromises. By a 63-32 margin, conservatives want elected officials not to compromise. Republicans simply don’t trust bipartisan deals.

It’s an ideological trait that goes beyond mere hatred for Obama, which is considerable. During the Bush years, why did the conservative base revolt against immigration reform but not the prescription-drug entitlement? Surely one reason, aside from the substance of the two bills, is that immigration reform was a bipartisan effort with the high-profile involvement of right-wing hate figure Ted Kennedy, while the prescription-drug bill was rammed through Congress on a partisan basis.

The conservative revolt against compromise expresses itself constantly. It comes through in the ever-present trope of citing the length of legislation as a primary reason to oppose it. It likewise comes through in the way conservative intellectuals routinely attack bills as a "stew of deals, payoffs, waivers, and special-interest breaks" — which is to say, they hate the fact that passing bills in Congress requires cutting deals with disparate constituencies, which is how legislation works.In other words, Republicans' real opposition is not to the substance of legislation at all, but to any cooperation with Democrats. In some ways, this viewpoint is not new. I am reminded of Richard Hofstadter's Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, in which he remarks:

The fundamentalist will have nothing to do with all this [the normal politics of compromise]: it is essentially Manichean; it looks upon the world as an arena for conflict between absolute good and absolute evil, and accordingly it scorns compromises (who would compromise with Satan?) and can tolerate no ambiguities. It cannot find serious importance in what it believes to be trifling degrees of difference: liberals support measures that are fol all practical purposes socialistic, and socialism is nothing more than a variant of Communism, which, as everyone knows, is atheism.

The difference is that today this attitude has taken over the entire Republican Party. This once again shows the problems with combining a presidential system of government with something increasingly approaching parliamentary-style party discipline. In a parliamentary system, this would not necessarily be a problem. In a parliamentary system, all power rests in a single legislative body with tightly disciplined parties. No one attempts bipartisan compromise, the "in's" simply enact their program without consulting the "out's." It is assumed that if the In's ran on a particular platform, they will draw up legislation entirely by the In's without consulting the Out's and pass it with all the In's voting yes and all the Out's voting no. The main check on passing anything too crazy is that the In's know if they do anything too crazy, they will lose the next election.

Such tight party discipline does not work so well under a presidential system because of its many veto points. For any measure to pass, it must have the support of the House, the Senate and the President. Any one of them can block any measure. In fact, with the rise of the routine use of the "filibuster," we have added that new veto point that any measure must have a 60% supermajority in the Senate, and that means 60 absolute votes, not just 60% of those present. When one party, let alone both parties, develops a parliamentary-style discipline, that means that legislation becomes impossible unless one party controls not only the House, the Senate and the Presidency, but at least 60 seats in the Senate. That is simply an insane way of running a country.

Republicans quite simply have what conservatives claim to despise -- a sense of entitlement, in this case to political power. When the Democrats hold the Presidency, Senate and House, Republicans want their representatives to block all action and make the country ungovernable. When the Republicans hold any one of these (in this case, the House), they want it to translate into complete power. The real reason they are angry at Cantor is that he could not parley control of the House into complete control of the government, but ended up making a deal with Democrats who controlled the Presidency and Senate. If that is the Republicans' goal, it is one they are unlikely to achieve, making these last two years ones of ever increasing anger and frustration. Rough seas ahead.

Labels:

dangerous polarization,

Election,

Partisan politics

Wednesday, June 11, 2014

And Another Thought on Right Wing Populists

All right, I have a few more reflections on the right wing populists who have been so successful in the recent EU elections, including a possible refinement of my definition of right wing populism. I have commented before that populists don't fit very well on the conventional right-left spectrum. The usually lean left on economic issues and right on social issues. They both punch up and kick down. Identifying populists as right wing or left wing is therefore a relative matter.

The populists who are on the rise in Europe are a classic example. The both punch up at Eurocratic elites and kick down at immigrants. The Guardian article naturally is most alarmed at these parties' tendency to punch up at the Eurocratic elite. But in this, they are doing no worse than the Eurocrats deserve. The Eurocrats have imposed the euro on an unwilling public and thereby prevented appropriate adjustments by falling currencies; they have egregiously mismanaged the financial crisis; they have inflicted senseless pain on member states and have nothing to offer but ever more pain and empty promises; and they have even overridden the democratic process in some countries to impose policies more to their liking. It is entirely appropriate to punch up at such an elite. Besides, the elites are not in danger from mobs in the; they are quite capable of protecting themselves. The article says precious little about right wing populist parties' eagerness to kick down at immigrants, many of whom are not capable of protecting themselves and are in danger from violent acts.

Likewise the Guardian is so spectacularly obtuse as to define turning left as not Eurosceptic, i.e., not punching up at an entirely appropriate target. Interestingly enough, such countries include Greece, Spain, Portugal and Italy, i.e., the Mediterranean countries that have suffered most from the EU's destructive policies. Italy has actually suffered the indignity of seeing the EU depose a democratically elected Prime Minister and replace him with someone more to their liking. By all means, let us applaud these countries to the extent they are refraining from kicking down at immigrants. But if they aren't as mad as hell at the Eurocrats, what's wrong with them?

Still, it does give me some further food for thought as to defining right wing populism. (A favorite subject of mine). It is my hypothesis that typical populist movements both punch up and kick down, and that whether they are defined as right wing or left wing is simply a matter of which is emphasized more. I further proposed that there are pure left wing populist movements that punch up only and do not kick down, but they usually have limited appeal. Still further, I proposed that there could hypothetically be pure right wing populist movements than only kicked down and did not punch up, but that as a practical matter, they do not seem to occur in the real world. But maybe we should define right wing populists versus left wing populists not only by whether they punch up (invariably they do), but what sort of target they punch up at.

Recall Jonathan Haidt's definition of conservatives -- they are people who value in-group loyalty, respect for authority and tradition, and reverence for the sacred. (Liberals, by contrast, are people who do not value these things). So when populists punch up, perhaps we should look at whether they are punching up along these lines. Do the denounce elites who are outsiders infringing on our in-group's autonomy and sovereignty? Elites who threaten traditional values, or lack respect for the sacred? It may be that this is a specifically right wing form of punching up, as opposed to left wing punching up which is resentment of elites who economically exploit us, or simply who are wealthier than we are.

Something to think about.

The populists who are on the rise in Europe are a classic example. The both punch up at Eurocratic elites and kick down at immigrants. The Guardian article naturally is most alarmed at these parties' tendency to punch up at the Eurocratic elite. But in this, they are doing no worse than the Eurocrats deserve. The Eurocrats have imposed the euro on an unwilling public and thereby prevented appropriate adjustments by falling currencies; they have egregiously mismanaged the financial crisis; they have inflicted senseless pain on member states and have nothing to offer but ever more pain and empty promises; and they have even overridden the democratic process in some countries to impose policies more to their liking. It is entirely appropriate to punch up at such an elite. Besides, the elites are not in danger from mobs in the; they are quite capable of protecting themselves. The article says precious little about right wing populist parties' eagerness to kick down at immigrants, many of whom are not capable of protecting themselves and are in danger from violent acts.

Likewise the Guardian is so spectacularly obtuse as to define turning left as not Eurosceptic, i.e., not punching up at an entirely appropriate target. Interestingly enough, such countries include Greece, Spain, Portugal and Italy, i.e., the Mediterranean countries that have suffered most from the EU's destructive policies. Italy has actually suffered the indignity of seeing the EU depose a democratically elected Prime Minister and replace him with someone more to their liking. By all means, let us applaud these countries to the extent they are refraining from kicking down at immigrants. But if they aren't as mad as hell at the Eurocrats, what's wrong with them?

Still, it does give me some further food for thought as to defining right wing populism. (A favorite subject of mine). It is my hypothesis that typical populist movements both punch up and kick down, and that whether they are defined as right wing or left wing is simply a matter of which is emphasized more. I further proposed that there are pure left wing populist movements that punch up only and do not kick down, but they usually have limited appeal. Still further, I proposed that there could hypothetically be pure right wing populist movements than only kicked down and did not punch up, but that as a practical matter, they do not seem to occur in the real world. But maybe we should define right wing populists versus left wing populists not only by whether they punch up (invariably they do), but what sort of target they punch up at.

Recall Jonathan Haidt's definition of conservatives -- they are people who value in-group loyalty, respect for authority and tradition, and reverence for the sacred. (Liberals, by contrast, are people who do not value these things). So when populists punch up, perhaps we should look at whether they are punching up along these lines. Do the denounce elites who are outsiders infringing on our in-group's autonomy and sovereignty? Elites who threaten traditional values, or lack respect for the sacred? It may be that this is a specifically right wing form of punching up, as opposed to left wing punching up which is resentment of elites who economically exploit us, or simply who are wealthier than we are.

Something to think about.

Labels:

dangerous polarization,

Election,

euro crisis,

Failures of Democracy,

General macro,

populism

EU Elections: The Elite Gets What it Deserved

And at last I return to what I promised to post about -- Europe's elections of EU representatives. Right wing populists have done very well. The establishment is running around wailing and wringing its hands, wondering how we could have come to this. The establishment has no one to blame but itself. It made a series of serious mistakes and prefers to ask the public to make ever greater and greater sacrifices, rather than admit that it was wrong.

It began with the euro. The euro was a cherished project of European elites, deeply distrusted by the general public. It should be obvious by now that the ignorant masses were right and "enlightened" elites were wrong about the euro -- it really was an intolerable violation of national sovereignty. Granted, the public was right for the wrong reasons. In the absence of a trans-national currency, the most stressed countries can let their currencies fall and export their way out of trouble. The process is painful, but not disastrous. It also violates elite and public intuition, which says that falling currencies are bad and to be avoided. But being wrong about the euro is forgivable. Everyone is wrong sometimes. Refusing to undo the euro is forgivable. The process might be so messy that even the current situation is preferable. But goddamit, even countries like Poland that benefited from not being in the euro want to get in. Even Iceland, which not only benefited from being outside the euro, but had a semi-revolution, wrote a new constitution, and prosecuted the bankers, the @#$%^!! authorities still want to get into the euro!

Since the crisis broke, mistake has compounded mistake, following a familiar script from Europe in the 1930's, Latin America from the 1980's, Asia from the 1990's, etc. Each time, conventional wisdom has called on countries facing massive capital flight to put wooing capital at the top of their priority list. Cut spending, shred the safety net, fire everyone with a good paying job, make sacrifices and ever more sacrifices, inflict general economic devastation on one's self to win the approval of international investors. Yet inexplicably, no one ever seems to want to invest in economic devastation. This is conventional wisdom. All respectable people agree to it. Is it any wonder, then, that if the only people who question the need to keep following failed policies, to keep inflicting ever more pain, to insist that lowered bond ratings are the be-all and end-all and that the human consequences are of no importance, are well outside the respectable mainstream, that such parties are gaining in popularity?

People are forgetting the whole purpose of the European Union in the first place. It grew out of the horrors of WWII and the hope that closer integration would prevent future wars and nationalism. But then again, the horrors of nationalism, of fascism, and (ultimately) of WWII arose from the Great Depression and the conventional wisdom among all respectable people of the day that more sacrifices and ever more sacrifices were what was called for. When respectable people could not deliver, but public turned to the disrespectable -- to fascists and other dictators. Is that what we want to see happen again?

I outsource my comments to Paul Krugman:

It began with the euro. The euro was a cherished project of European elites, deeply distrusted by the general public. It should be obvious by now that the ignorant masses were right and "enlightened" elites were wrong about the euro -- it really was an intolerable violation of national sovereignty. Granted, the public was right for the wrong reasons. In the absence of a trans-national currency, the most stressed countries can let their currencies fall and export their way out of trouble. The process is painful, but not disastrous. It also violates elite and public intuition, which says that falling currencies are bad and to be avoided. But being wrong about the euro is forgivable. Everyone is wrong sometimes. Refusing to undo the euro is forgivable. The process might be so messy that even the current situation is preferable. But goddamit, even countries like Poland that benefited from not being in the euro want to get in. Even Iceland, which not only benefited from being outside the euro, but had a semi-revolution, wrote a new constitution, and prosecuted the bankers, the @#$%^!! authorities still want to get into the euro!

Since the crisis broke, mistake has compounded mistake, following a familiar script from Europe in the 1930's, Latin America from the 1980's, Asia from the 1990's, etc. Each time, conventional wisdom has called on countries facing massive capital flight to put wooing capital at the top of their priority list. Cut spending, shred the safety net, fire everyone with a good paying job, make sacrifices and ever more sacrifices, inflict general economic devastation on one's self to win the approval of international investors. Yet inexplicably, no one ever seems to want to invest in economic devastation. This is conventional wisdom. All respectable people agree to it. Is it any wonder, then, that if the only people who question the need to keep following failed policies, to keep inflicting ever more pain, to insist that lowered bond ratings are the be-all and end-all and that the human consequences are of no importance, are well outside the respectable mainstream, that such parties are gaining in popularity?

People are forgetting the whole purpose of the European Union in the first place. It grew out of the horrors of WWII and the hope that closer integration would prevent future wars and nationalism. But then again, the horrors of nationalism, of fascism, and (ultimately) of WWII arose from the Great Depression and the conventional wisdom among all respectable people of the day that more sacrifices and ever more sacrifices were what was called for. When respectable people could not deliver, but public turned to the disrespectable -- to fascists and other dictators. Is that what we want to see happen again?

I outsource my comments to Paul Krugman:

[T]he European elite remains deeply committed to the project [the euro and European Union], and, so far, no government has been willing to break ranks. But the cost of this elite cohesion is a growing distance between governments and the governed. By closing ranks, the elite has in effect ensured that there are no moderate voices dissenting from policy orthodoxy. And this lack of moderate dissent has empowered groups like the National Front in France, whose top candidate for the European Parliament denounces a “technocratic elite serving the American and European financial oligarchy.”I also highly recommend this piece on how the center-left is committing suicide by insisting on placing European integration ahead of domestic well-being.

Labels:

euro crisis,

Failures of Democracy,

General macro

Tuesday, June 10, 2014

And Another Reminder Why Private Armies are Not So Great

So, it appears that Jerad and Amanda Miller, the couple who killed two Las Vegas police and a store manager were supporters of the Patriot movement and participants in the Clive Bundy standoff. According to the Bundys, they were asked to leave because of their radicalism and felony record. Other observers say there were nothing to distinguish them from any other supporters present. But one way or the other, this should once again be taken as a warning as to why private armies dedicated to violent revolution are not the best protectors of liberty in a country with a democratically elective government.

So let me give the usual disclaimers here. Most Fox New/Tea Party right wingers are not militia members. Most militia members do not go on mad shooting sprees. But both groups need to police their fringes a whole lot better. Rachel Maddow brilliantly pointed out that when Fox News was so energetically championing Clive Bundy, it had ample evidence readily available that he held extremely radical views that presumably neither Fox nor most of its viewers shared. Yes, one can deplore federal heavy-handedness toward someone with odious views. But too close an embrace tends, after all, to imply affection. And while militia members are quick to dismiss people like the Millers as a few bad apple and assure us that most of their crew are peace and freedom loving, such protestations are naive. Combining an ideology of fear and loathing (regardless of the targets of that fear or loathing), constant warnings about the possible need to resort to violence, and lots and lots of guns is a positive invitation to bad elements to infiltrate your movement. To pretend otherwise is to close one's eyes to reality. The assumption that elective government is simply tyranny waiting to happen while private armies are necessarily champions of liberty is simply not convincing.

At the same time, I would give a piece of advice to my own side. Don't panic. Remember, crime rates are continuing to fall. Remember, all combined acts of right wing terrorism aren't enough to add up to even a blip in the total crime rate. And besides, panic is what fuels the whole Patriot movement. Don't let it fuel us, too.

So let me give the usual disclaimers here. Most Fox New/Tea Party right wingers are not militia members. Most militia members do not go on mad shooting sprees. But both groups need to police their fringes a whole lot better. Rachel Maddow brilliantly pointed out that when Fox News was so energetically championing Clive Bundy, it had ample evidence readily available that he held extremely radical views that presumably neither Fox nor most of its viewers shared. Yes, one can deplore federal heavy-handedness toward someone with odious views. But too close an embrace tends, after all, to imply affection. And while militia members are quick to dismiss people like the Millers as a few bad apple and assure us that most of their crew are peace and freedom loving, such protestations are naive. Combining an ideology of fear and loathing (regardless of the targets of that fear or loathing), constant warnings about the possible need to resort to violence, and lots and lots of guns is a positive invitation to bad elements to infiltrate your movement. To pretend otherwise is to close one's eyes to reality. The assumption that elective government is simply tyranny waiting to happen while private armies are necessarily champions of liberty is simply not convincing.

At the same time, I would give a piece of advice to my own side. Don't panic. Remember, crime rates are continuing to fall. Remember, all combined acts of right wing terrorism aren't enough to add up to even a blip in the total crime rate. And besides, panic is what fuels the whole Patriot movement. Don't let it fuel us, too.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)