|

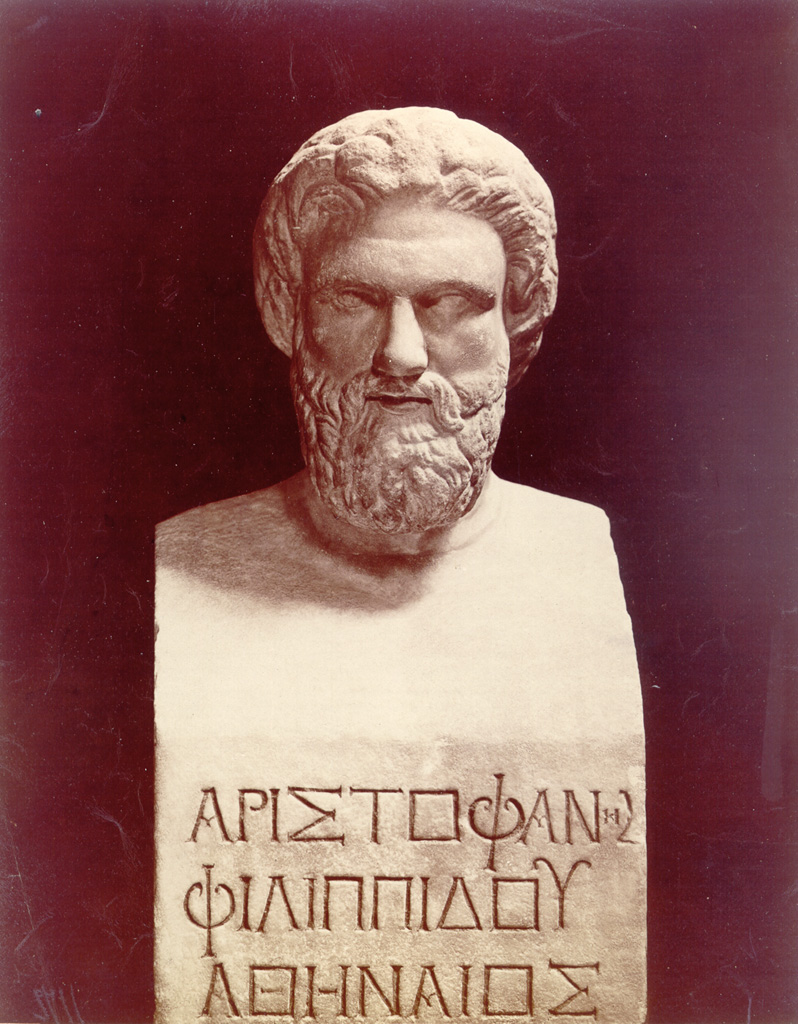

| Aristophanes |

Athens would later develop professional speech writers, who would prepare speeches to be given to the Assembly, or to juries (the Athenians were very litigious), which would serve as our major source of information on everyday life in Athens. But in the 5th Century BC this still lay in the future. Our main source of information on everyday life in Athens of the day, and how the democracy actually worked in practice, if from Aristophanes. Needless to say, a comic playwright every bit as wacky as William S. Gilbert is not a reliable source. But, as with Monty Python, surprisingly accurate information (in a sort of non-literal way) can peep through the many layers of nuttery.

Which leads to his play The Wasps. This may be the first recorded instance of anyone referring to addiction as a disease. It begins with two slaves keeping an old man locked up in his son's house to keep him from indulging his terrible disease, i.e., his addiction. But not the usual addictions to gambling or alcohol or high living. No, the old man is addicted to jury service.

Which calls for some back story. In ancient times, and until quite recently, sons were expected to support their parents in their old age. In Classical Athens, this was an obligation enforceable by law, and some failings as a father were punishable by forfeiture of the right of support. But it is never a comfortable situation. As a child, the father is the provider and the son the dependent; the father the authority and the son the bound to obey. But when a son supports his aged parents, he is the supporter and the parents the dependents; the son has the power, but the father is supposed to retain the authority. Such a situation is made to order for conflict.

So, when Pericles began offering pay for jury service, a lot of old men were eager to accept. The pay was probably less than even an unskilled job would offer, and certainly no more, but having a little money in their pocket offered old men some of the independence and dignity that they had lost, and a chance to exercise real authority. It also encouraged Athenians in their general litigiousness and (Aristophanes charges) made it easier for sleazy politicians to bring unfounded charges against their rivals. (He also hints that some poor men were quitting their day jobs to be full-time professional jurors, but my understanding is that that did not become common until later).

In his previous play, The Clouds, Aristophanes used a son beating his father to represent the overturning of the moral and social order, the very embodiment of all that is shocking. In Wasps, a son is forcibly restraining his father and locking him in the house, and we are expected to take the son's side. After the old man is thwarted in various comic attempts to escape, he and his son start talking about it. The old man likes the pocket money and power that go with being on a jury. The son tries to persuade him that he is just abetting corrupt politicians like Cleon. But his father just can't give up the addiction, so the son arranges for him to try the family dog, Labes for stealing a Sicilian cheese. Labes is accused by a rival dog, Cleoncur, with various kitchen utensils serving as witnesses. (See what I mean about Aristophanes' Gilbertian wackiness?)

|

| Lyre |

But what is with the dog that never learned to play the lyre? My translator ended up throwing up his hands in despair, saying that he had no idea what Aristophanes was talking about, the comment was complete nonsense, and that might be the point, since Aristophanes was a master of nonsense. Speaking as a non-classical scholar, my own guess is that if the trial of Labes the Dog really does represent the trial of Laches the General, the reference is probably topical. Maybe Laches never learned to play the lyre and used his lack of musical talent to burnish his regular guy credentials with his jurors, most of whom never learned to play the lyre either. This is pure guesswork on my part, obviously, but at least it makes sense. The translator points out, though, that this is one of those happy coincidences in which something may work better in translation than in the original. In English, there is an obvious pun, not present in Greek, on play the lyre and play the liar. So if the dog pleads that he is a simple, uneducated dog who never learned to play the lyre/liar, that comment becomes a lot more pungent than Aristophanes intended. (And to be more pungent than Aristophanes intends is a spectacular feat, indeed). In fact, it works a little too well in English. The double meaning could be conveyed to a reader of the play, but to convey it on stage, one would have strum a lyre conspicuously or the audience would never pick up on Aristophanes' intended meaning at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment