As Ahriman leads Martie into his inner sanctum and shuts the sound proof door, we can expect some serious exposition. As we suspected, Ahriman is using his mind control powers to make Dusty and Martie feel strangely, even suspiciously, calm in his presence. We see demonstrated what was at most

faintly hinted at before. Ahriman gained control over Martie by spiking her coffee in the waiting room. He sound proofs his office so no one will know what he is doing to his patients inside. He has a private waiting room outside his office so no one else, like the receptionist or other patients or family members, will see him come out and take control of the person waiting. And I will have to admit that if Dean Koontz had taken my advice and postponed revealing Ahriman as the villain until his characters found out, all of this would be more difficult to reveal. But the exposition leaves some important things unanswered. It fails to explain Martie's

mysterious phone call. In fact, it directly contradicts what we have been told before by saying that it was not until Martie's visit to the office yesterday that Ahriman implanted in her an intense fear of her own violent potential. Yet Martie clearly started showing such fear

before going to Ahriman's office, and even before his never-explained phone call. None of this is ever addressed.

Once Ahriman has Martie alone in his office, he takes control. He doesn't ask for voyeuristic details of her phobia thus far, but merely works on worsening it. He shows her pictures of mutilated bodies and tells her to memorize them and see them in her next panic attack. He tells her that sadism is our true human nature, but even under his deepest spell, he cannot keep her from having compassion for the mutilated victims he shows her.

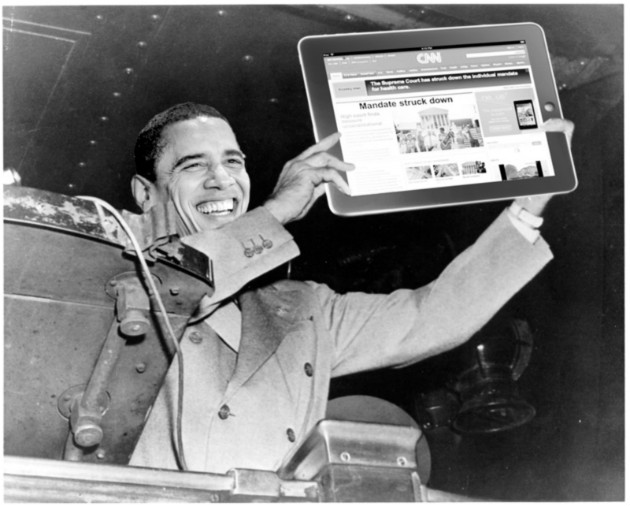

Dusty, in the meantime, is in the waiting room with the mysterious book that Martie thinks she has been reading, but really has not. It is pristine and has never been opened. But up till now our focus has been solely on the creep factor that she thinks she has been reading the book without really reading it. Up till now that has distracted us from the actual contents of the book. In fact, the contents have been entirely besides the point, so far as we know so far. It is

The Manchurian Candidate.

![]()

It seems incredible that Dusty would never have heard of this classic, but maybe I am just showing my age. It is, of course, about brain washing and mind control. (It is also a fantasy. The sort of mind control the novel portrays is not possible). And, much to Dusty's astonishment, it even features a character named Dr. Yen Lo. As Dusty reads in fascination, looking for clues as to Skeet's condition, he hears the click of the inner office door opening. He leaps to his feet and throws the book aside, fearing being caught with it. This would appear to suggest that he already suspects Ahriman at some level, or why would he be afraid of being seen with the book? Be that as it may, Ahriman now reveals what has long been screamingly obvious -- Dusty is under his control.

At this point, Ahriman offers a bit of exposition. After assuming control of Martie, he had her drug Dusty's desert and conducted the programming sessions at their house. Martie, under his control, could easily be put to the side. He hooked Dusty up to an IV bottle which is apparently necessary to achieving proper control. Valet the dog was much to sweet natured to be a good guard dog, so Ahriman just shut him up in the study with a yellow squeaking Booda duck. This is a good bit of exposition. It very nicely explains Valet's alarm whenever anyone starts to be under mind control.

It does leave a minor question open. Apparently programming sessions call for hooking the victim up to an IV bottle. That necessarily calls for some extended privacy without danger of interruption. That was easy to do in Ahriman's office with Susan under mind control and out of the way, or in Dusty and Martie's house, with Martie under mind control and out of the way. But how did Ahriman get sufficient privacy to go through three programming sessions with Susan? His first session with Susan took place at

his own house after she completed the sale, when he toasted the sale with

champagne, spiking hers. But how did he

get close enough to conduct the other two programming sessions? We don’t find

out.

Ahriman also reveals that he knows how Dusty stopped Skeet’s suicide, but hasn’t

given up wanting to make Skeet kill himself.

How does he know? Presumably he

asked about it during that

other mysterious phone call when Dusty Caught the Dog Napping. But we never find out. It would only have taken a line or two, but

Koontz doesn’t bother. For that matter,

how did Ahriman know he would find Dusty home alone at that particular

time? Presumably he wouldn’t want to

exercise telephonic control when both spouses were home, or the one who didn’t

answer would notice the other one was acting

very strangely. Maybe he

ordered Dusty to be home at a certain time, and Martie to stay with Susan until

after that time. But we aren’t

told. Maybe I shouldn't complain that Koontz gave away the game too soon. If he had only revealed Ahriman as the villain when Dusty and Martie found out, think how much

more exposition he would have had to pack into even less pages.

Then Ahriman makes another blunder. After telling Dusty not to interfere with

Skeet’s next suicide attempt, and to get Martie to his office on Friday, he

then tells him, “You will return to the outgoing waiting room, Dusty. Pick up the book that you were reading and

sit where you were sitting before. Find

the point in the text where you were interrupted . . . all recollection from

the moment I stepped out of m office, just after you heard the click of the

latch, will have been erased.” He should

have erased Dusty’s memory until just before

he heard the click of the latch, not until just after. To hear the click of

the latch about to open and then not see the door open is a bit odd. To hear the click of the latch, throw aside

the book and leap to your feet, and then be sitting with the book in your hand,

the door solidly closed, is a good deal stranger. Didn't Ahriman notice that Dusty was throwing away the book and leaping to his feet when the door opened?

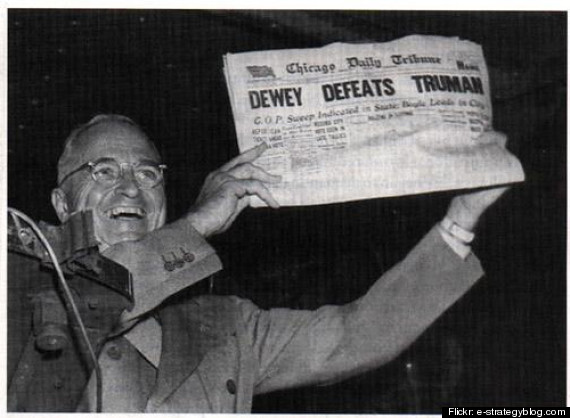

So, Dusty hears a click, throws away the book and leaps to his feet -- and then finds himself again sitting with the book in his hands. It greatly alarms him. Clearly, he is missing more time, as if a

celestial editor erased some moments from the videotape of his life. “Apparently, an apprentice editor with a lot

to learn.” But Ahriman is no

apprentice. How could he make such a

rookie mistake. And why doesn’t the

sudden lapse of memory in Ahriman’s

office direct Dusty’s suspicion to Ahriman?

I know, because Ahriman programmed him not to suspect. But really!

In any event, Dusty read that the brainwashed soldier in The Manchurian Candidate goes into a trance when someone tells him,

“Why don’t you pass the time by playing a little solitaire?” He plays until he sees the queen of diamonds,

and then becomes controllable. Dusty

supposes that the same thing is happening, except with a name from the novel

and a haiku. He calls his foreman and

tells him to pick up Martie’s prescription for Valium and a book of haiku. He is also convinced that the appearance of

the book is no coincidence. Someone must have given it to her to

clue her in to what is happening.

Martie emerges from Ahriman's office feeling better. Ahriman has told her to feel no more than a vague uneasiness, with brief spells of sharper fear about every hour. But at 9:00, she is to have the worst panic attack yet. Martie, of course, is unaware of any of this. She and Dusty leave with great admiration of Ahriman, and only vague forebodings about why.

Tea Party

Tea Party