|

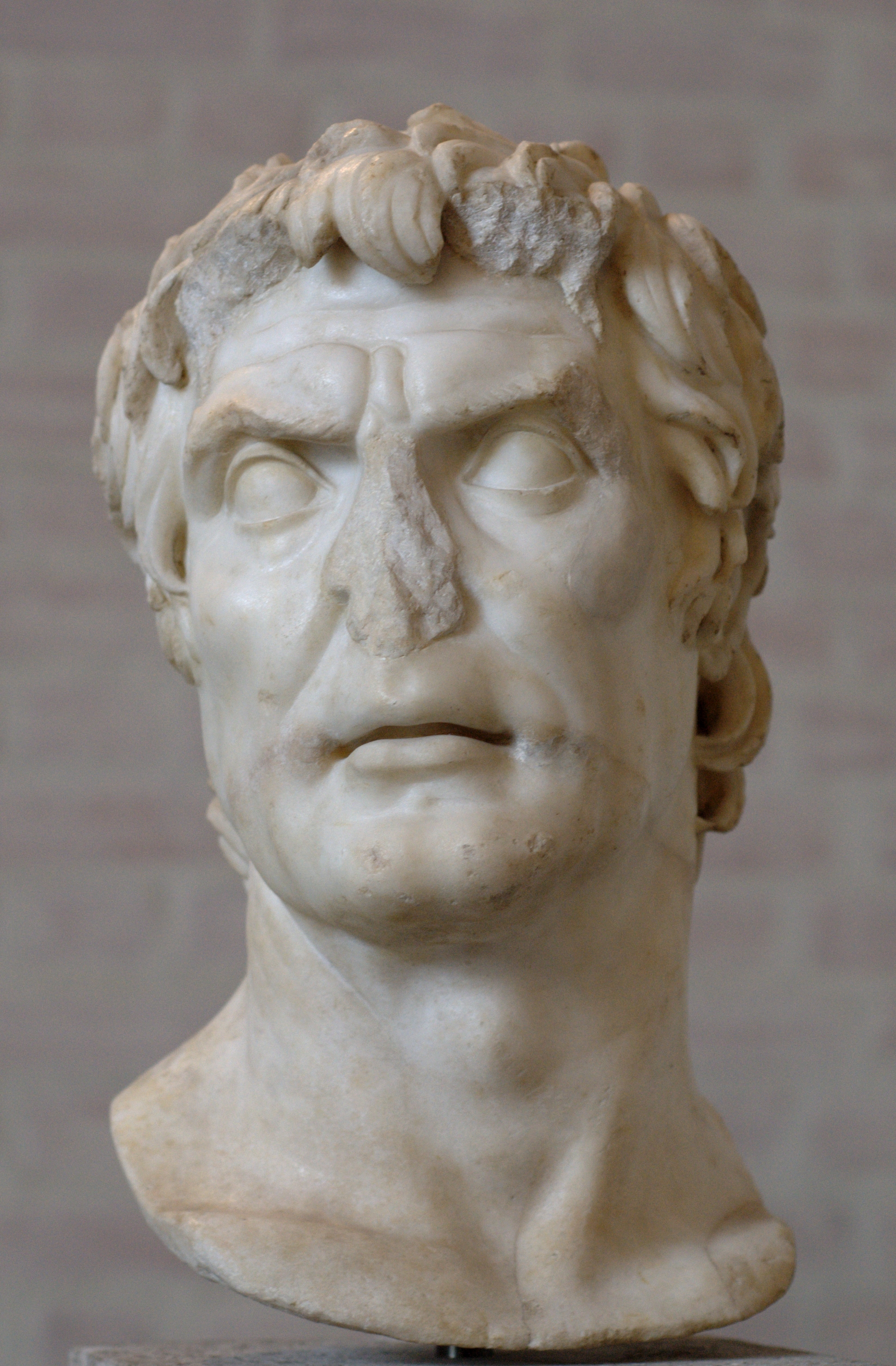

| Sulla |

In the first two books, the author goes out of her way to emphasize that Sulla is very handsome. This is apparently based on his bust which is, indeed, quite handsome, at least with the paint worn off. Plutarch describes his complexion as splotchy, so much so that his enemies said he looked like a mulberry sprinkled with meal. Plutarch also says that during his war in the east, Sulla had a numb and heavy feeling in his feet that he took as a sign of gout and so took a hot springs cure.

There is also another bust of Sulla, much older and less attractive. McCullough, a neuroscientist, takes this to mean that Sulla was prematurely aged by a terrible illness. She takes the numbness and heaviness in his feet as signs of diabetes, which caused him to gain and lose an immense amount of weight, ruining his beauty. In the early books he is so fair as to be almost albino and very prone to sunburn. The author has his mulberry look result from a terrible sunburn and further burning from the hot spring. He has gone from ungodly handsome to human wreck and become somewhat warped as a result. He has also taken to heavy drinking because nothing else relieves the itching.

Interestingly enough, although Sulla is not a household name on the level of Nero or Caligula, the author does portray him as a sort of degenerate Roman Emperor, much like one might portray Nero or Caligula. Erratic and temperamental, he loves acting even more erratic than he really is and tormenting the people around him with fear and keeping them forever guessing what he might do next. Only Pompey is too thick-skinned to be intimidated. Outwardly, he seems a bit crazy. Soon it becomes clear that he is crazy like a fox. Upon retiring, he behaves just like a degenerate Roman Emperor and goes off with his theater friends to live a life of wild excess in luxury, food, drink, and sex, alternating with attacks of serious illness (driven, in large part by his excesses) and violent fits of rage. Over time, the partying binges become less and less common and the sickness and rage more and more common and he dies horribly, vomiting blood.

|

| Alexander the Great |

So how does the fictional Pompey compare to the historical record? My guess is that McCullough is being less than just to him. On the other hand, Plutarch's biography, at least for these early years, reads like a whitewash. Despite his generally conservative sympathies, Plutarch ignores a whole lot of traditions that Pompey flouted, such as demanding a triumph when he had not held any public office, running for consul when he had not held any office or even been in the Senate, and refusing to disband his army until he got his way. Portraying

him as bribing a large faction in the Senate to his bidding appears to be a slander by McCullough.

|

| Pompey (see any resemblance?) |

Setting aside the real Pompey as unknowable, McCullough's Pompey certainly makes his personality felt. He comes across as self-centered, over confident, crude, insensitive, fond of giving offense, and so arrogant as to make even Caesar look good by comparison. But he does have considerable ability in war and administration, charm of a manipulative type, and a way of making his wives happy.

When we first meet him, he has bribed a judge into letting him off by marrying his daughter, makes her happy in their marriage, and then casts her off as soon as a better opportunity comes along. He presents his army to Sulla with maximum high-handedness, making demands that Sulla's other followers consider an appalling lack of respect. But Sulla tolerates him because he wins battles. Twice Sulla gives him as wife the widow or forcibly divorced wife of a political opponent, much against her wishes. Twice Sulla wins his wife over, the first one with sickeningly sweet flattery, the other by respecting her mind and opinions. He is so coarse that when Sulla says that Pompey, his father, and his infant son should be called the Butcher, the Kid Butcher, and the Baby Butcher, Pompey doesn't even notice that he has been insulted. He uses his army to exert political pressure, though only as a bluff, not really meaning it. Fighting wars in Africa and Spain, he arrogantly presumes to lecture men who have fought there much longer on the lay of the land. Then he loses some battles and gets some arrogance kicked out of him, at least for the time being. His lack of education and polish show up in the dispatches he writes home, which scandalize some Senators, while others applaud his plain style for plain truths.

In the end, he overreaches politically as well as militarily. He wants to parlay his wealth and military might into political power unbounded by law and custom and, indeed, in defiance and scandal of it. But he doesn't want to go so far as to be a military dictator. He wants to outrage the Senate and rub their noses in his power, but a military dictatorship wouldn't do that properly. If he established a military dictatorship, the Senate would submit but take comfort in knowing that his power was built on force only and that they submitted only out of coercion, as with Sulla. He wants the Senate to accept his power as necessary and legitimate, even as they hate it. Sulla likes being feared and learns to accept being hated. Pompey wants to be loved. And since he also wants the Senate to hate him but be forced to accept his power, his natural affinity is as a populist. But it is an unfamiliar hat to Sulla's man. Besides, like Marius, Pompey is a much better general than he is a politician.

Enter Caesar. Though quite unhistorical, he negotiates a settlement between Pompey and Crassus in which they share the consulship in exchange for restoring power to the tribunes and getting them to pass a pardoning them for any treason they may have committed. Pompey uses his huge wealth to offer extravagant entertainment. He proves a good administrator. Knowing such games are accompanied by outbreaks of crime and disease, he hires retired gladiators to maintain order and puts up signs everywhere warning people not to relieve themselves outside a public latrine, and reminding them of the importance of hand washing and eating only fresh food. (!) Outbreaks of crime and disease are averted. But politicking has exhausted him, and at the end of his term, Pompey his happy to return to private life.

No comments:

Post a Comment