|

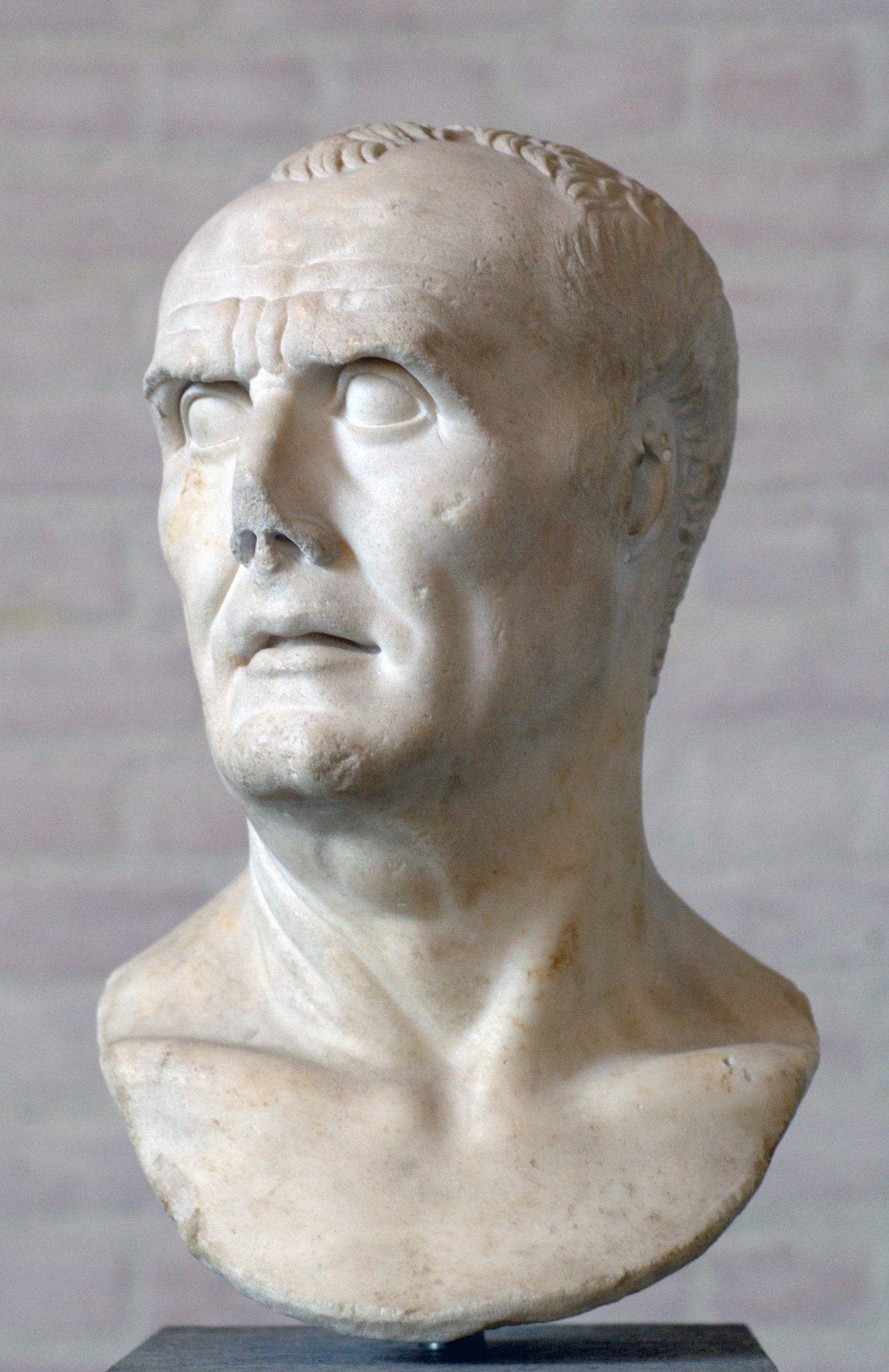

| Marius |

Sulla begins his consulship quite reasonably. War has

devastated Italy. The economy is in ruins. Debts are unpayable. Between the expense of the war and Drusus' currency debasement, there has been major inflation and interest rates have skyrocketed. There is widespread outcry to cancel debts. An earlier politician tried to outlaw interest and was torn asunder by outraged bankers (or at least a mob hired by outraged bankers). Sulla makes a reasonable compromise. He recognizes that to cancel debts or abolish interest will wreck Rome's credit system, and that to insist in payment in full will cause universal bankruptcy. So he allows only simple interest and only at the original rate, a significant concession given the inflation that has taken place. Although in most lawsuits the parties are required to post bond equal to the amount in dispute, he authorizes the judge to waive bond in suits for debt. No one is very happy with the compromise, but all recognize it as necessary. He says that he opposes extending citizenship to the Italians, but will respect the law and allow all citizenship extended to stand. It is hard to find anything to criticize there.

Then Mithridates of Pontus, taking advantage of Rome's weakened condition, seizes large amounts of the eastern empire and massacres every Roman and Italian in the territory he has captured. Rome has a war on its hands that it is in no condition either to fight or to finances. Sulla desperately scrambles to get resources together and grapples with the very real problem of how to finance the war. Marius, showing increasing signs of derangement since his stroke, demands to be given command and is overruled due to his age and ill health. He also dismisses practical concerns about how to finance operations.

And then there is Sulpicius. He is introduced as a conservative tribune, so conservative that he vetoes the sensible suggest to recall everyone banished for proposing such citizenship. He had zealously fought in the civil war and been implicated in its worst atrocities. When Pompey the Cross-Eyed Butcher celebrated his triumph but did not have a foreign king to parade through the streets, Sulpicius rounded up Italian children orphaned by Pompey's wars, marched them through the streets in the parade, and then threw them out of the city and left them to their fate. But Mithridates' massacres change his viewpoint. If foreigners make no distinction between Roman and Italian, he concludes that his whole perspective was wrong. Suddenly he assumes the role of a demagogue, railing against Rome's ruling class.

Is this justified? On the one hand, Rome's ruling class had resisted admitting the Italians to citizenship, leading to a ruinous civil war that left Italy in ruins and culminated in the Italians becoming citizens anyhow. Then a hostile foreign leader took advantage of Rome being weakened by civil war to seize many Roman possessions and massacre all Romans and Italians in his power. So on one hand yes, Rome's rulers have clearly let the people down, and the people have legitimate reason to be angry with them. On the other hand, in refusing Italian citizenship and setting off this ghastly chain of events, Rome's leaders were doing exactly what public opinion wanted them to, so really the people of Rome had no one to blame but themselves.

Sulpicius undertakes several measures. One is to recall everyone exiled for supporting Italian citizenship, which is certainly reasonable. One distributes Italians and freedman among all the Roman tribes. This is popular among the Italians, who are seeing their power made proportionate to their numbers. It is popular with Rome's urban residents because many of Italians and freedmen are urban dwellers who will increase the city's strength. But it is unpopular among the rural tribes who see their voting strength diluted. It is controversial but defensible. But he also proposes to expel from the Senate anyone with debts over quite a modest sum. The practical upshot is that the Senate will not be able to muster a quorum. Remember the important functions of the Senate -- authorizing expenditures, appointing provincial governors, foreign and imperial affairs. To destroy such an important part of the government without finding anything to replace it is not just radical, it is completely crazy.

A shrewd observer of the scene contrasts Sulpicius with Saturninus, the chief demagogue in the last crisis. Saturninus rose to power in a time of food shortages. His primary constituency were the poorest Romans because they were most effected. His goal was his own power. Sulpicius, by contrast, can to power at a time of excess debt. Since the poor have little debt (and most of it in the informal sector), his primary constituency is the middle class. His goal is not to advance his own power, but to overturn the power of Rome's current rulers.

Unable to seize power on his own, Sulpicius seeks Marius' support. Marius, who didn't hesitate to crush Saturninus in the last book, agrees on one condition -- that he be given command of the army in the East. Sulpicius agrees and ads this to his measures. When the measures meet with resistance, Sulpicius sends armed me in to the forum and violence breaks out. Sulla's co-consul and the co-consul's son are killed. Sulla goes to Marius' house to try to reason with him and finds Marius in no mood to talk. There is no doubt left -- Marius has become deranged and cares for nothing but his own command, regardless of who he harms in the process. Sulla leaves, but prepares to exercise Second Amendment solutions.

No comments:

Post a Comment