I want to make a brief digression here to address another question: Can one write a saintly character who is also a sexual being? The best example I can think of is Robert Bolt's A Man for All Seasons, a play about Sir Thomas More, emphasizing his larger-than-life, unyielding integrity. More's wife and (oldest) daughter appear in the play, emphasizing that he is a family man as well as a saint. So I should acknowledge the possibility. But A Man for All Seasons is decidedly the exception and not the rule. Saintliness and sexuality appear a problematic mixture.

Uncle Tom's Cabin, again, is notorious in this regard. Tom is often criticized as being asexual, and this is attributed to racial anxiety. Interestingly enough, we first meet him surrounded by his wife and children, but the scene is unconvincing and leaves us with a queasy feeling. His aura really is overwhelmingly an asexual one, and the attempt to provide him with a wife and children to meet the 19th Century cult of domesticity goes most disturbingly against the grain. No doubt racial anxiety played a part here, but given the asexual nature of literary saints in general, probably only a part. We may dismiss the asexual lama in Kim as an old and feeble monk, as well as reflecting Kipling's general hostility toward women. Riverworld is a different matter. In Riverworld, everyone is resurrected 25 years old, in perfect health, and sterile. There is no disease, and no one ages. All of which positively cries out for a frenzy of sexual indulgence, which is exactly what we get. People do end up pairing off and taking long-term mates, including the Chancers. The Sufis, however, remain unmated, and strangely asexual in a world where sex is flaunted everywhere.

Likewise, our hero, Jean Valjean, is an (almost) entirely asexual character, with no wife or lover. Still, the book comments, as "nature is a creditor that accepts no protest," he does harbor carnal feelings for his adopted daughter at an unconscious level. Also, when he takes her away from the abusive innkeeper, he gives a a black dress to wear in mourning for her mother. After she stops these garments, he keeps them in sweet preservatives to cherish, and after she marries, lays them out and weeps. It seems a bit creepy. However, this is the only hint we see of this celibate ever having a sexual nature. So it would appear that a saint can be a sexual being, but the portrayal is so difficult that most literary saints remain asexual.*

None of this serves as a barrier to saintly characters being physical. The Sufis in Riverworld, after all, are as young and healthy as everyone else, one tall and strong, the other small and lithe. Tom's asexuality is often explained by making him a feeble old man, but this is not what Stowe had in mind. He is described as "a large, broadchested, powerfully-made man." Jumping into the river to save a drowning girl, he is "broad-chested and strong-armed." The slave trader advertises him as "broad-chested, strong as a horse." Even the aged Lama is a Tibetan who proves a vigorous mountain climber and loves to leave the trails to test his strength against a steep slope (a thing he later confesses as sinful worldliness).

But Valjean is the most physical of all these asexual heroes. He has superhuman strength. A movie I previously saw attributed his strength simply to the life of a convict at hard labor -- work in the rock quarries makes them very strong, if they survive it. But the novel makes clear that his strength far exceeds that of the normal convict as hard labor. He was much stronger than his fellow inmates, who call him Jean the Jack. He is so strong that when a balcony collapses, he holds it up on his shoulder until workmen arrive. He can crawl under a cart sinking in the mud and lift it on his back. When a sailor (and sailors are strong) is dangling from a rope, unable to climb back up, Valjean bursts his chains with a single hammer blow, lowers himself on another rope, fastens the sailor to himself, and then climbs back up, hand-on-hand, lifting both their weight. When the wicked innkeeper corners Valjean in the woods, intending extortion, he gets a glimpse of the man's strength and thinks the better of it. When the villains capture him, it takes eight people (seven men and a muscular woman holding his hair) to subdue him. And, of course, he carries his son-in-law unconscious for miles through the sewer. He is also as agile as he is strong and can scale any wall. (Hence his numerous escapes). He is also a remarkable marksman. When the men at the barricades need a mattress, Valjean brings down a mattress hanging from a window by shooting out the supporting ropes.** And he has extraordinary tolerance for pain. When the bad guys try to make him give up his daughter's location by menacing him with a red-hot iron, he shows his contempt for the threat by taking it and voluntarily burning himself.*** But physical prowess does not necessarily translate into sex appeal.**** For all his physical prowess, Jean Valjean has none.

So, why can a saint-hero be intensely physical, but not sexual? I can think of two reasons, one being that sex is part of our animal nature that the saint-hero rises above, and the other that the obligations of family stand in the way of true saintliness -- that have special obligations to a small group of people weakens the saint's universal benevolence.

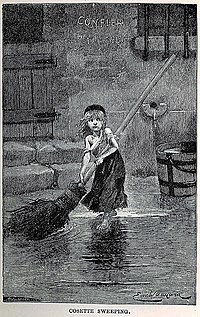

The second explanation is both strengthened and weakened when saint-heroes do undertake family obligations. Tom's family makes only a brief appearance at the beginning and plays no further role in the story. The Lama, by contrast, regards Kim as his son and ends up foregoing nirvana in order to return and bring salvation to Kim as well. Valjean, of course, acquires an adopted daughter, Cosette. Cosette is described as the only person he ever loved, and this love is clearly seen as part of his spiritual growth. Yet at the same time, it is part of his shrinking and becoming more narrow. Before Valjean finds love, he is a factory owner. He brings prosperity to a town, funds schools, establishes retirement funds, endows a new wing of the hospital, establishes a pharmacy, and becomes mayor. He also comforts mourners, pulls carts out of the mud, distributes alms to the poor, gives peasants tips on farming, teaches children to make new toys, and breaks into houses to leave gold pieces. As mayor, he prevents lawsuits and reconciles enemies. In short, he makes the world a better place, or at least his little corner of it. As father of an adoptive daughter, his vision is never so grand. He is a loving father and gives alms to the poor, but no longer strives to make the world better. (Being a convict on the run and afraid of being found out may play a role too, of course). As factory owner, he grapples with the terrible dilemma of keeping going all the improvements he has made, or keeping an innocent man from going to prison in his place. As father, he deals with the much simpler dilemma of protecting his son-in-law or keeping his daughter for himself. The narrowing of vision is immistakable, but it does not diminish Valjean in his author's eyes.

Then there is the matter of Valjean's relationship with Cosette's mother, Fantine. Fantine is a poor girl who becomes the lover of an unscrupulous man and has a child out of wedlock by him. When her lover deserts her, the disgrace of her daughter's illegitimacy causes her to leave the child in the care of the innkeeper Thernadier and seek her fortune on her own. At first, she works in Valjean's factory. Valjean has women work in a separate shop from men to prevent little incidents of the type Fantine has, and delegates management of the women's shop to a woman to avoid even the appearance of impropriety. Unfortunately, he chooses a woman manager whose notions of propriety go too far, and who throws Fantine out in the street when she finds out about her past. Shunned by all respectable society, Fantine is forced into prostitution and is dying of consumption (no doubt brought on by poverty and cold) when Valjean finds her. He does appear to take a special interest in protecting her. It is certainly not a carnal interest -- Fantine is dying, after all. But what is the nature of their relationship. An earlier movie I saw treats it as a tender but chaste love, making Cosette their spiritual daughter. Other interpretations assume that he is simply protective of Fantine, and later her daughter, because he has inadvertently wronged them. As for Fantine, there can be little doubt that she is at some level in love with Valjean. Hers is the love of a woman who has known nothing from men but betrayal and abuse finally meeting a man who can be trusted -- a mixture of hero worship and gratitude at finding a man with no carnal interest in her. Could their relationship have developed in a more carnal interest if she had been well? We will never know. But, once again, if Valjean had taken a wife, he would have experienced the same narrowing of vision that he did upon adopting a daughter.

In the end, however, I can only conclude that particularized love for a small subset of people is important enough to most people that authors (including Hugo) are not altogether willing to deny it to their saint characters. So I am inclined to rely more on the former explanation -- that a saint occupies a higher spiritual plane than the rest of us, and that sexuality is part of the baser nature that saints must leave behind. Or at least so it must seem to an author constructing a saint.

This digression out of the way, I want to return to the question of my last post, as raised by the New Yorker reviewer: what is this innocent and saintly man forever seeking to atone for.

PS: Maybe I should also add Julius Caesar from George Bernard Shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra. Shaw's Caesar, though noble, is too frivolous and light-hearted to be a classic saint. Nonetheless, Shaw describes him as a character intended to have virtue and therefore not need goodness. He is not forgiving because he is too great to resent. He is not frank because he feels no need for discretion. And he is not generous in giving away wealth because it means nothing to him. And, although Shaw does not add it, he is immune to Cleopatra's charms because he has no sex drive. (The real Caesar, by contrast, was said to be "Every woman's husband and every man's wife.")

_________________________________________________

*Should I throw in a note about Melanie here? Melanie is a married woman and nearly dies in the birth of a child conceived while her husband is on leave. Afterward, they abstain for years, fearing that she will not survive a second birth. But motherhood is so important to her that ultimately she risks it again and dies of complications of her second pregnancy. So we must concede that Melanie is at least sometimes sexually active. But to say that she lacks sex appeal would be putting it mildly.

**Javert mentions Valjean's marksmanship as well as his strength as one of the ways he recognized him as an escaped convict? But how would he know about a convict's marksmanship, which he presumably has never seen?

***Infection later sets it, and it takes a month for him to be well enough to go out again, but the bad guys don't have to know.

****Nor is sex appeal necessarily the same as sexuality. Mr. Roark on Fantasy Island has so much sex appeal that the air crackles everywhere he goes, yet the character is strictly asexual and never takes any interest in a woman. In Mr. Roark's case, it appears to be not so much because he is a saint, but because he is an angelic power above the weaknesses of the flesh.

No comments:

Post a Comment