Irving Fisher

Irving FisherPaul Krugman has provided a link to a paper by Irving Fisher, apparently dated 1933, setting forth his debt deflation theory of depressions. I must confess, this was the first time I actually read Fisher as opposed to reading about him. Fisher's essential theory of great depression is that they are caused by too much debt building up in the system and then all having to be paid down at once. It is a sub-category of the credit bubble theory.

Any discussion of Fisher has to compare and contrast with a closely related but decidedly different credit bubble approach to business cycles – the Austrian School. The Wikipedia proposes that the two are complementary halves of a whole – the Austrians show the credit bubble building up, while Fisher shows it crashing own.

Up to a point, their differences are mostly matters of emphasis. Austrians emphasize bad investments, presumably in the sense of physical investment, that must be shaken out. Fisher emphasizes bad investments made with borrowed money, which lead to bad debts. Austrians emphasize too-easy credit as the sole cause of bad investments. Fisher agrees that easy credit is one possible source of bubbles, but not the only one. Another source, depressingly, is inventions and technological improvements leading to very real investment opportunities. In 1837, the culprit was canals spanning the Appalachians, leading to a vast expansion in trade. In 1873, it was a railroad boom.* In the 1920's it was presumably the manufacture of consumer durables. In other words, even without too-easy credit, prosperity and technological innovation are in and of themselves dangerous because they can easily give way to irrational exuberance.

However, their views on a remedy are diametrically opposed. The Austrians might agree with Fisher that bad debts are a major part of the problem, but their response is to call for the debts to be paid off or, as Ron Paul puts it, “debt liquidation.” Fisher’s truly original insight is that such attempts are counterproductive. If everyone starts liquidating debt at the same time, the result is to shrink the economy, cause it to become deflationary and thereby raise the debt burden.

The graph below clearly bears out Fisher’s views. It makes clear that the debt level in 1929 was, in and of itself, manageable. The real spike in debt relative to GDP occurred only after the Depression set in and nominal GDP fell precipitously. Furthermore, as soon as nominal GDP began to recover, the relative debt burden fell just as impressively. This makes clear why nominal GDP is every bit as important as real GDP -- debt cannot exist relative to real GDP, only relative to nominal GDP.

It also explains why Fisher and the Austrians disagree on price stability. Both emphasize its importance, but for opposite reasons. Austrians have an absolute horror of inflation and consider avoiding it to be the defining feature of economic health. So great is the Austrian fear of inflation that they attribute the Great Depression to the "inflationary" boom of the 1920's, even though consumer prices actually fell during that time. Their explanation is that if the Federal Reserve had not been overly expansionary, prices would have fallen even more.**

It also explains why Fisher and the Austrians disagree on price stability. Both emphasize its importance, but for opposite reasons. Austrians have an absolute horror of inflation and consider avoiding it to be the defining feature of economic health. So great is the Austrian fear of inflation that they attribute the Great Depression to the "inflationary" boom of the 1920's, even though consumer prices actually fell during that time. Their explanation is that if the Federal Reserve had not been overly expansionary, prices would have fallen even more.**Fisher, at least in the essay above, does not so much as mention inflation. His great fear is of deflation, which magnifies debts. His remedy was "reflation," or reversing deflation to bring debt back to a manageable level. Far from believing, as the Austrians do, that there is an inevitable bottom that must be reached and any attempt to avoid it merely prolongs the agony, Fisher describes this as “the so-called ‘natural’ way out of a depression, via needless and cruel bankruptcy, unemployment and starvation” and says that insisting that the economy reach an inevitable bottom is “as silly and immoral . . . as for a physician to neglect a case of pneumonia.”

Much of this sounds like what just hit our economy, especially the excess debt part. Other portions sound like things we fortunately avoided, particularly the deflation. Unless you count deflation of asset prices, a subject Fisher does not discuss. In other words, not only are bad investments being made with borrowed money, leading to bad debts, but bad (and often speculative) investments are being made with borrowed money, backed by inflated asset prices. Once asset prices fall back to earth, suddenly good debt becomes bad because it is no longer backed by adequate collateral.

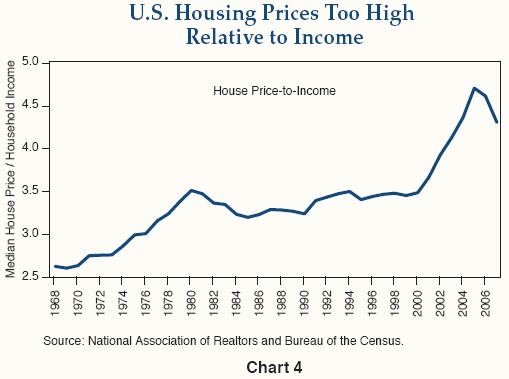

It is odd that Fisher did not discuss this subject because it famously happened in the 1920's. It had happened many times earlier in land bubbles and other speculative bubbles. And, of course, it has happened just recently. As the graph above makes clear, our debt level today dwarfs the debt level of 1929, 0r even 1933.*** We have avoided falling into deflation this time around -- at least, wage and price deflation. But asset prices, especially housing prices, have deflated, leaving a lot of suddenly unsecured or under-secured debt. There is no need to "reflate" wage and price levels because they have not fallen. It also makes little sense to reflate housing prices, since those had become clearly excessive relative to the prices of everything else.

This raises an obvious question. If debt levels are insupportable now, even without wages and prices falling into deflation, and if deflation of the housing that backs our excess debt is necessary in order to bring housing prices realistically in line with income and rental values, where do we go from here?

Would Fisher be willing to go a step beyond mere "reflation " and endorse outright inflation as a way of shrinking debts down to manageable levels?

________________________________________

*The 1837 and 1873 depressions are also neat opposing illustrations of interaction of credit and real investment opportunities. The 1837 depression was caused by irrational exuberance over canals and trans-Appalachian trade, with a bubble abetted by too-easy credit (Jackson de-chartering the national bank and distributing it deposits among private banks). The 1873 depression was caused by irrational exuberance over railroads, with the collapse of the bubble aggravated by too-tight credit (the gold standard).

**And here I must confess to not remembering why Austrians think inflation is so bad. However, during the Depression Hayek definitely blamed it on the inflationary boom of the 1920's, although he later acknowledged he was wrong. Murray N. Rothbard was still doing so in the 1960's.

***I will note that the source of the debt to GDP graph above mentioned that much of the expansion in debt was financial debt, i.e., debt owed by banks to other banks. This is generally considered less dangerous than other forms of debt because it is a mere reshuffling of money among banks. Excluding financial debt, the expansion of debt is not quite as scary.

No comments:

Post a Comment